This post is published in collaboration with Elrha.

This year’s International Women’s Day theme is #ChooseToChallenge, encouraging people to call out gender bias and inequality around the world. Gender bias and inequality are reflected in systematic imbalances, including in the humanitarian aid system.

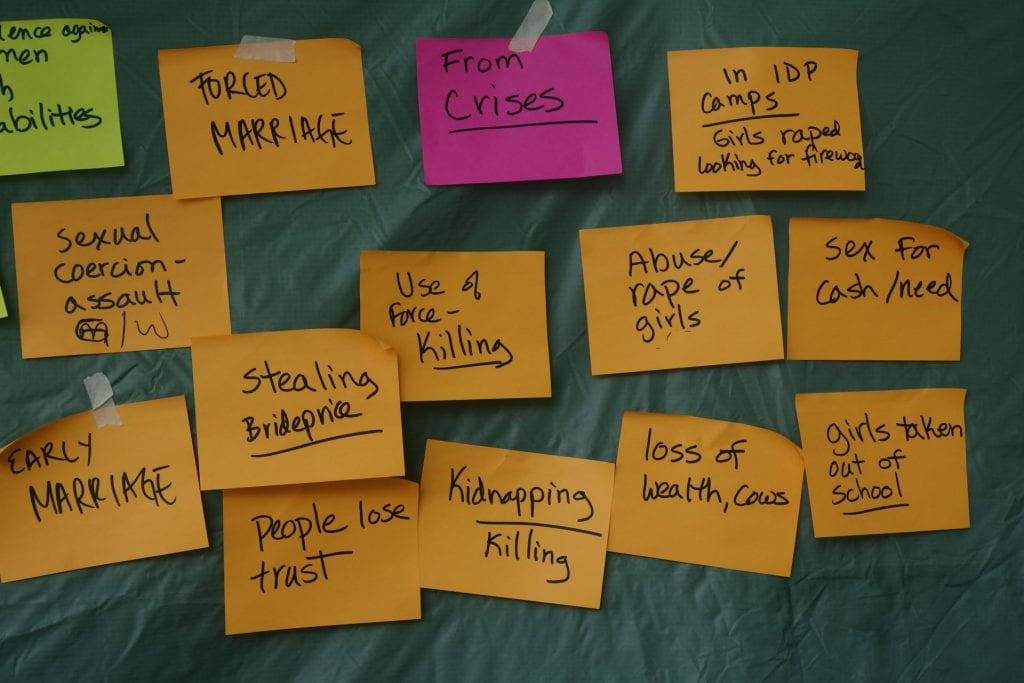

Our recently-released report – Gap Analysis of Gender-based Violence in Humanitarian Settings: A Global Consultation – highlights that many of the challenges affecting the delivery of effective gender-based violence (GBV) programming are systematic in nature, reflecting the wider de-prioritization of GBV programming within humanitarian action. It also acknowledges that all GBV, or violence against women and girls, is rooted in patriarchal gender norms and power imbalances.

GBV is a pervasive issue facing women and girls in times of humanitarian crisis. As the COVID-19 pandemic has spread globally, a parallel pandemic of GBV has also been affecting the lives of women and girls, who may be isolated with their abusers, affected by increasing stress and poverty, and unable to seek needed help and support.

Despite these increasing needs, humanitarian aid appeals remain chronically underfunded and the funding gaps for GBV programmes are consistently larger than other humanitarian sectors.

Addressing gender biases and inequality in GBV must be a collective endeavour

The challenge of GBV in humanitarian action is cross-cutting. All organisations delivering humanitarian aid are tasked with working together to reduce the risks of GBV being perpetuated. While further effort is needed to change behaviour and norms stemming from gender biases, many humanitarian aid workers outside the GBV sector do not know how to effectively reduce risks of GBV within their programming or appropriately support a woman or girl who discloses she has experienced violence.

GBV programming is still seen as the remit of specialists – rather than a life-saving priority that should be fully integrated in all humanitarian action.

This Gap Analysis report brings attention to these systemic gaps in humanitarian action and highlights specific areas where more attention is needed – including increasing funding, ensuring the commitment of senior leadership to promoting GBV risk mitigation activities throughout all sectors, and introducing or strengthening accountability mechanisms – to ensure GBV programming is mainstreamed throughout humanitarian response.

Furthermore, it calls for greater systematic shifts in how the aid sector functions by calling out the need to prioritise empowering local women’s organisations and civil society to lead on issues of GBV prevention and response within humanitarian response.

Reasons to be hopeful

On a positive note, many global stakeholders such as the GBV Area of Responsibility and the Call to Action on Protection from GBV in Emergencies, have consistently drawn attention to GBV during humanitarian crisis, and have had considerable success in raising the profile of GBV as a life-saving aspect of humanitarian response. They, among many others, have provided essential guidance and tools to facilitate the humanitarian community to be better able to address GBV in emergencies

Despite the many challenges identified in the Gap Analysis, there are reasons to be hopeful. In development settings, programming models such as Raising Voice’s Get Moving! curriculum take a prevention-oriented approach to training, and focus on organisational culture change.

Furthermore, new efforts such as the Paris School of Economics and partners’ work to address gender biases within humanitarian programming may inform our understanding of these biases and enable us to explore means to overcome them.

While the report only briefly touches on issues of sexual exploitation and abuse, the issues being brought to light through the #AidToo movement, as well as wider efforts to recognise systematic racism and inequalities globally, are clearly linked to the work of the GBV community. This work aims to raise awareness and address the situation facing women and girls.

Hopefully, these efforts will continue building momentum and lead to change within aid systems. Those creating and implementing GBV programmes must develop more robust and transparent accountability structures that answer not only to practitioners, researchers, donors and innovators but to the women and girls they seek to support.

Maureen Murphy is a Research Scientist with the Global Women’s Institute at George Washington University. Previously, she has worked with numerous international non-governmental organizations, including in South Sudan with the American Refugee Committee and in Sierra Leone with GOAL Ireland. Prior to this, she worked with the Child Protection in Crisis Network based at Columbia University to coordinate locally driven child protection and gender based violence research projects in Africa and Asia. Maureen holds a Master’s in Public Health from Columbia University and has a professional interest in improving monitoring and evaluation in complex emergencies, particularly in the realm of gender based violence and reproductive health programming. She is a published author on a variety of gender based violence and reproductive health topics.

Be First to Comment