I’ve been slumming for more than 15 years, wearing my best smile and my oldest clothes, drawn to areas of deliberate neglect in African slums. In early August, I traveled to Nairobi along with my SMPA colleague, Steven Livingston. We met with a group of community leaders in Mathare, a slum on the east side of Nairobi.

Communities such as Mathare and Kibera in Nairobi are points of entry for internal migrants from the Kenyan countryside. Increasingly they are empowered by the connective technology of mobile phones and social networking sites like Facebook. As we saw in August, these slums are often frothed by rising expectations. Residents want to do more than be “on the map.” They want education and access to opportunity, skills, and jobs. They would like more attention from their elected officials.

Mathare was a site of violence after the disputed election of 2007, when a banned organization called Mungiki waged battle with Kenyan security forces and over a hundred people were killed. More recently Mathare has received more benign attention from the government. The slum now has electric lines running along one of its major streets, and young uniformed members of the National Youth Service now work on ad-hoc projects. There is a community center and a small soccer pitch between the buildings.

Mathare has been extensively mapped and surveyed by Spatial Collective, a local company which is run by GW graduate Primoz Kovacic. His crew surveyed almost 1,000 households in 2014 and found that mobile phone penetration was 93 percent. Perennial problems in Mathare include a severe shortage of toilet facilities and huge piles of trash dotting the outskirts of the slum and filling the spaces between the corrugated iron dwellings. Municipal trash pickups are confined to downtown Nairobi, and some residents dump in the river which runs through the slum.

Other problems include rampant abuse of an illegal brew, changaa, which translated means “kill me quickly” and can have toxic ingredients in it. Glue sniffing among young men is common. Mathare also has unemployment rates running over 80 percent.

Ann Wanjiru runs a small volunteer organization in Mathare called Touch Their Hearts which provides legal aid to battered wives and cares for orphans in the slum. Her thankless work is supported by contributions, and she could use more help.

In Kibera, which some have called the largest slum in Africa, entrepreneurs like Abzed Osman offer walking tours to international visitors. UN-Habitat has built some housing which backs up along the railroad tracks running through Kibera. On the tour he did with me, Abzed pointed out a biogas extraction facility, a large circular building where for a few pennies one can use a restroom. We visited a workshop that makes jewelry out of camel and cow bones, and he took me back home to meet his mother.

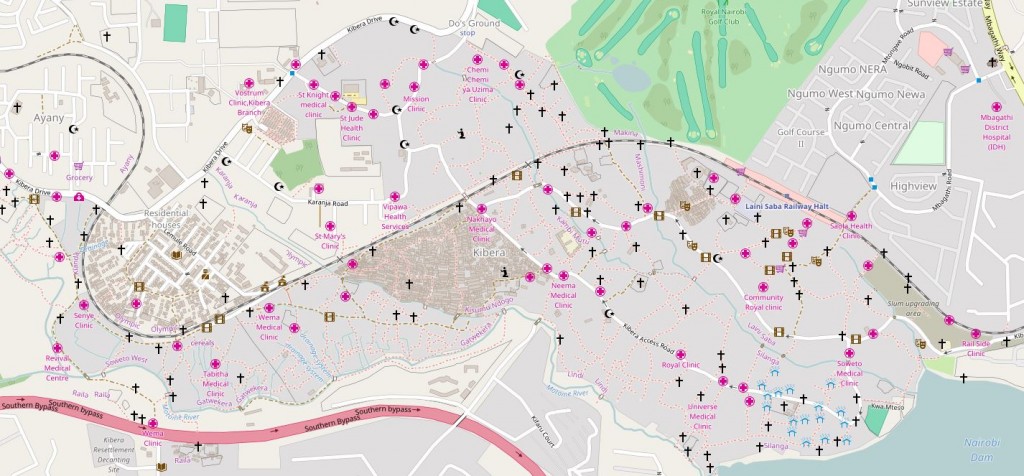

Kibera became something of a household word in development circles after Map Kibera began a project to digitize streets and other features of the sprawling slum. There are countless volunteer development organizations which put out their shingles and raise money from international charities. These entities are known locally (and rather pejoratively) as “briefcase NGOs,” because they seem to disappear quickly after taking money and leaving no lasting trace.

"We have lived here for more than a century."

Community resilience manifests in participation in activist groups, or in an affiliation with a charismatic church or mosque. There appears to be widespread cynicism about the efficacy of projects such as Map Kibera, which in the locals’ view advanced the careers of some Western development professionals but didn’t change life meaningfully for most slum residents. While perhaps unfair, the charges implicate a certain eye-in-the-sky mindset which puts slums on the map but then goes no further.

How can outsiders help the residents of these forsaken places? One way is to visit, meet people, and network. I am now Facebook friends with a number of slum dwellers. More meaningful action would be international support for citizen empowerment and recognition from local and national governments that the slums are legitimate places to live. “We have lived here for more than a century,” one of my new Facebook friends wrote. It’s about time that their land claims and their aspirations find a footing.

~ David Rain is an Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs at The George Washington University.