Rose Kleiman

December 11, 2017

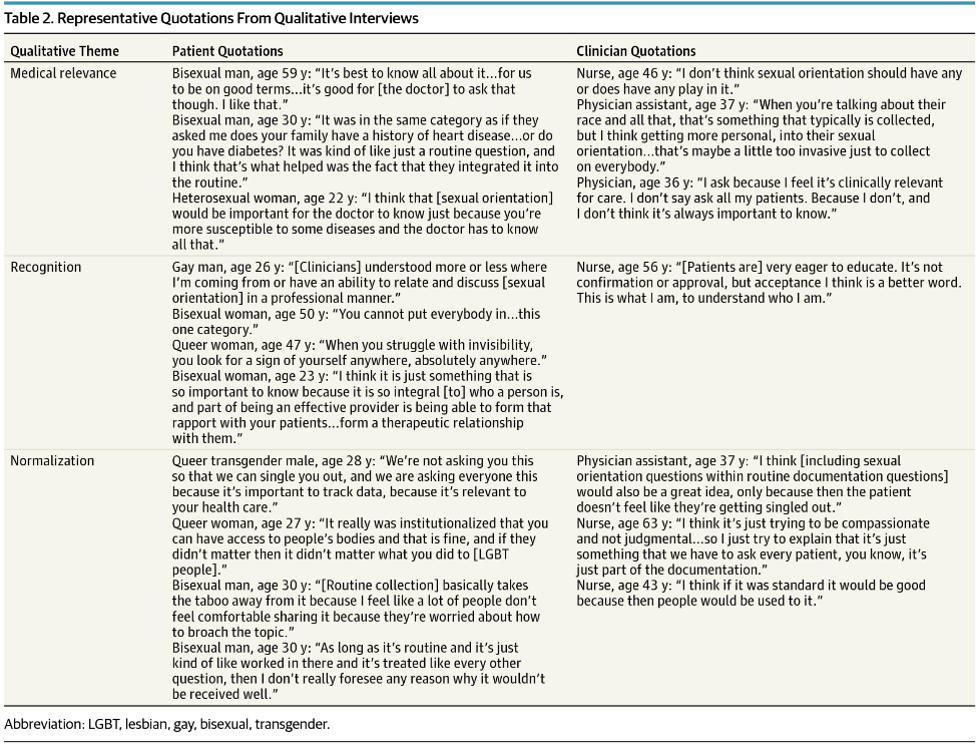

Many healthcare systems are trying to find innovate ways to help lower the use of emergency departments (EDs). Often, the focus is on “superutilizers”, patients who frequent the ED many times a year. This cohort of patients only encompasses about 5% of all ED patients, but accounts for about 25% of all ED visits yearly. [i] Reasons for being a frequent user of the ED are multifactorial including complex medical conditions and challenging socioeconomic situations, but often results in more fragmented patient care and higher costs to the healthcare system.

A new study from the University of Tennessee[ii] aimed to help keep frequent ED users from needing the ED through the use of a patient navigator program. The research team created a patient navigator program that worked within the ED to help patients review diagnoses and prescriptions, arrange follow-up appointments and transportation, and identify relevant community resources. The navigator would meet with the patient to perform these tasks during the initial visit, any following ED visit, and by telephone within 2 weeks and 12 months of the initial visit.

Superusers were defined as any patient presenting to the Erlanger Baroness ED for their fifth visit or more within a 1-year period. Once a patient was properly consented for participation in the pilot, they were assigned to the control arm or the experimental arm. The control group also received a call from a research assistant at the 2 week and 12-month time post the initial visit to the ED.

At the two-week follow-up call, visits to a primary care physician (PCP) were reported in 47% of patients in the treatment group and 43% in the control. However, at the twelve-month follow-up, phone survey results found that the experimental group had seen their PCP an average of 6.42 visits (95% CI = 5.14–7.70) over the 12-month follow-up period, which was significantly more than the 4.07 visits (95% CI = 3.38–4.76) over the 12-month follow-up in the control group (p = 0.0013). This suggests that the navigator had a positive influence on getting patients to utilize their PCP to a greater extent.

Community ED visits decreased during the 12-month study period, compared to the 12 months prior to enrollment (2,249 visits prior to enrollment to 2,050 visits 1 year after enrollment, 8.8% decrease) study. While there was a decrease in in ED use in both arms of the study, there was a greater decrease in ED visits from the pre-enrollment year to post-enrollment year in the treatment group (1,148 visits to 996 visits, 13.2% decrease) compared to the control group. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: Emergency department visits pre- and post-enrollment

The research team reported that the cost of the patient navigator program was $34,808, which consisted of salary, benefits, and program administration costs. Overall health system costs (ED and hospital, excluding ED physician costs) for all 282 patients went from $3,925,233 in the year prior to enrollment to $3,130,510 in the follow-up 12 months (20.2% decrease; 95% CI = 19.5%–20.9%). While costs for ED visits did go down for both study arms, costs for ED visits had a greater decrease in the treatment group ($1,267,280 to $930,584, 26.6% decrease, 95% CI = 26.1%–27.0%) versus the control group ($1,556,536 to $1,283,590, 17.5% decrease, 95% CI = 17.1%–17.9%; p < 0.0001).

Only two other studies have looked at the use of a patient navigator program to help decrease frequent use of the ED and the results have been conflicting[iii] [iv]. But, the University of Tennessee team has shown with this pilot that patient navigators may be an effective way to reduce some of the frequent use and associated costs of the ED. The researchers do note that these findings could represent a placebo effect by entering the study alone might or could represent a regression to the mean for both groups.

As we continue to look for innovative ways to help some of the neediest patients is the healthcare system, patient navigators are uniquely positioned to play an integral role in the changing health care environment by facilitating access to care, as well as addressing language and cultural barriers and may be a key component of helping frequent users of the ED manage their healthcare and social needs.

[i] LaCalle E, Rabin E. Frequent users of emergency departments: the myths, the data and the policy implications. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:42–48.

[ii] Seaberg, D., Elseroad, S., Dumas, M., Mendiratta, S., Whittle, J., Hyatte, C., & Keys, J. (2017). Patient Navigation for Patients Frequently Visiting the Emergency Department: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Academic Emergency Medicine, 24(11), 1327-1333.

[iii] Spillane LL, Lumb EW, Cobaugh DJ, Wilcox SR, Clark SR, Schneider SM. Frequent users of the emergency department: can we intervene? Acad Emerg Med 1997;4:574–80.

[iv] Shumway M, Boccellari A, O'Brien K, Okin RL. Cost-effectiveness of clinical case management for ED frequent users: results of a randomized trial. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:155–64.

Rose Kleiman is a medical student at the GW School of Medicine & Health Sciences