Greg Jasani

October 16, 2017

Chest pain is one of the most common chief complaints of patients who present to emergency departments. It accounts for over 7 million visits and is the most common chief complaint in patients over the age of 65.[i],[ii] It is also presents a diagnostic challenge for emergency medicine physicians. The differential for chest pain is broad and includes deadly conditions such as myocardial infarctions and benign ones such as costochondritis. Due to fear of missing cases of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or acute myocardial infarction (AMI), many patients undergo lengthy ED workups or are admitted for further observation or testing. However, ultimately, only a small number of patients are found to have ACS or MI.[iii] One of the great challenges of emergency medicine is finding a way to efficiently and safely determine which patients need urgent intervention and which can be safely sent home.

The European Society for Cardiology guidelines recommend the use of a 0-hour/1-hour strategy (class 1 recommendation) where AMI is considered ruled out either if a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) is < 5 ng/L at presentation or if 0-hour hs-cTnT is < 12 ng/L together with a 0- to 1-hour increase < 3 ng/L.[iv] Several studies have demonstrated a very high negative predictive value for the 0 and 1 hour troponin rule.[v],[vi] However, some studies have shown a less than 99% sensitivity[vii],[viii], which has led to some questioning as to its usefulness as an adequate diagnostic tool. As a result, some have proposed combining the 0 and 1hour troponin rule with EKG data and the TIMI score to increase the sensitivity.

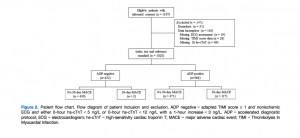

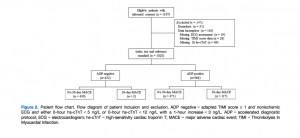

Mokharti et al sought to determine whether this combination was indeed a useful diagnostic tool for detecting AMI.[ix] Their study, published in Academic Emergency Medicine, is the first to evaluate whether the 0 and 1 hour troponin rule with an EKG and low TIMI score is a reliable tool to safely identify and discharge chest pain patients, which they referred to as the Accelerated Diagnostic Protocol (ADP). If the troponins and EKG were negative and the calculated TIMI score was < 1, the ADP would be considered negative and the patient would be considered low risk and potentially safe for discharge. Their study was a prospective observational study. Patients who presented with non-traumatic chest pain had a 0 and 1 hour troponin levels drawn as well as an EKG and calculated TIMI score. Although the ADP was not used to guide the management of these patients, the authors then determined if the ADP was predictive of risk.

The primary endpoint of this study was the presence of a Major Adverse Cardiac Event (MACE) within 30 days of initial presentation. In total, 1,020 patients were analyzed. MACE occurred within 30 days in 119 patients. The majority of these were AMI (n=77) or unstable angina (n=38). Among patients who were ADP-negative, only 0.5% of patients had a MACE; the ADP missed 2 patients who both had unstable angina. The ADP did not miss any patients who were experiencing an AMI during their visit.

One interesting point of discussion with regards to this study is their use of the TIMI score over the HEART score. The TIMI score is designed to identify patients at high risk of experiencing a MACE and even offers management guidelines. The HEART score, by contrast, is specifically focused on identifying patients at low risk of experiencing a MACE. Although a relatively newer risk stratification tool, the HEART score has been validated in multiple studies[x],[xi] and it has even been shown to be superior to the TIMI score in determining which patients are experiencing a MACE.[xii] Given that this study sought to identify and discharge low risk patients it would seem like the HEART score would fit in better with the ADP. The authors do not comment on their decision to use the TIMI score over other risk stratification tools. Whether the HEART score improves the results seen with the ADP is certainly worth investigating further.

One interesting point of discussion with regards to this study is their use of the TIMI score over the HEART score. The TIMI score is designed to identify patients at high risk of experiencing a MACE and even offers management guidelines. The HEART score, by contrast, is specifically focused on identifying patients at low risk of experiencing a MACE. Although a relatively newer risk stratification tool, the HEART score has been validated in multiple studies[x],[xi] and it has even been shown to be superior to the TIMI score in determining which patients are experiencing a MACE.[xii] Given that this study sought to identify and discharge low risk patients it would seem like the HEART score would fit in better with the ADP. The authors do not comment on their decision to use the TIMI score over other risk stratification tools. Whether the HEART score improves the results seen with the ADP is certainly worth investigating further.

With respect to the Mokharti study, it represents the first study to evaluate the performance of the 0 and 1 hour troponin rule-out strategy when combined with clinical risk stratification tools. The results of this study suggest that using the ADP could potentially lead to expedited identification and discharge of low risk chest pain patients. Of course, further studies will be needed to evaluate the ADP being used in actual clinical practice. Yet this study does raise the exciting possibility that, in the near future, low risk chest pain patients can be safely screened and cleared for discharge in an hour, leading to considerable savings for both patients and the healthcare system.

[i] National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Emergency Department Summary Tables. CDC. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2010_ed_web_tables.pdf.

[ii] National Center for Health Statistics. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2010 Emergency Department Summary Tables: Table 13. Twenty Leading Primary Diagnosis Groups for Emergency Department Visits, by Patient Age and Sex: United States, 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2010_ed_web_ tables.pdf. p. 5.

[iii] Penumetsa SC, Mallidi J, Friderici JL, Hiser W, Rothberg MB. Outcomes of patients admitted for observation of chest pain. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:873–7.

[iv] Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent STSegment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:267–315.

[v] Mokhtari A, Borna C, Gilje P, et al. A 1-h combination algorithm allows fast rule-out and rule-in of major adverse cardiac events. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1531–40.

[vi] Mokhtari A, Lindahl B, Smith JG, Holzmann MJ, Khoshnood A, Ekelund U. Diagnostic accuracy of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T at presentation combined with history and ECG for ruling out major adverse cardiac events. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:649–58.e3.

[vii] Mueller C, Giannitsis E, Christ M, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a 0-hour/1-hour algorithm in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction with high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:76–87.e4.

[viii] Pickering JW, Greenslade JH, Cullen L, et al. Assessment of the European Society of Cardiology 0-hour/1-hour algorithm to rule-out and rule-in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2016;134:1532–41.

[ix] Mokhtari A, Lindahl B, Schiopu A, Yndigegn T, Khoshnood A, Gilje P, et al. A 0-Hour/1-Hour protocol for safe, early discharge of chest pain patients. Acad Emerg Med 2017; 24(8): 983-992

[x] Backus B, Six A, Kelder J, Bosschaert M, Mast E, Mosterd A, Veldkamp R, ,et al. A prospective validation of the HEART score for chest pain patients at the Emergency Department. Intl J Cardiol 2003; 168(3): 2153-2158

[xi] Backus B, Six A, Doevendans P, Kelder J, Steyerberg E, Vergouwe Y. Prognostic Factors in Chest Pain Patients: A Quantitative Analysis of the HEART Score. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2016; 15(2): 50-55

[xii] Poldervaart J, Langedijk M, Backus B, Dekker I, Six A, Doevendans P et al. Comparison of the GRACE, HEART, ,and TIMI score to predict major adverse cardiac events in chest pain patients at the emergency department. Intl J Cardiol 2017; 227(15): 656-661

Greg Jasani is a fourth year medical student at the GW School of Medicine & Health Sciences