James Spearman

September 25, 2017

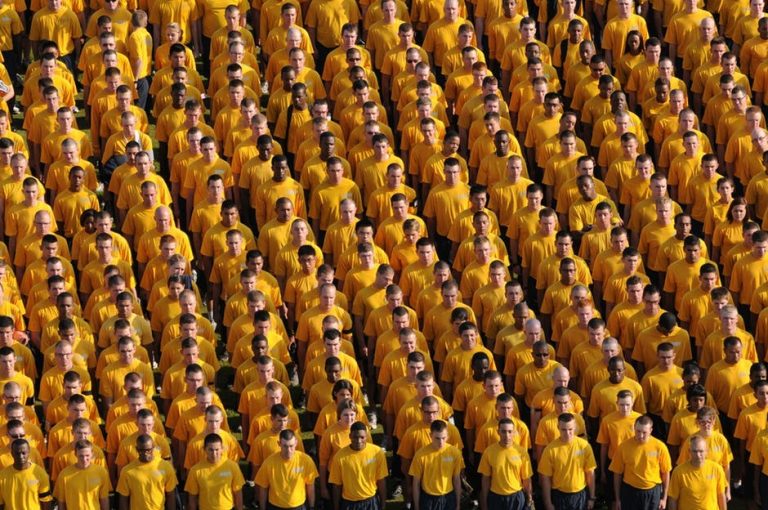

The EMS team bursts through the door while the patient moans in agony, raising the tension in the room. The medical team quickly moves the injured body from the stretcher to the bed. The junior resident at the head of the bed calls “airway intact” while trying to concentrate on breath sounds. The senior at the foot of the bed attempts focuses on the EMS report while he impatiently waits for the vitals to appear on the monitor. Another resident tears through the patient’s clothes to begin the FAST, trying to concentrate on the patient and the screen at the same time. Though not guaranteed, one of the five people mentioned is statistically likely to be suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). How can you tell? What are the signs? Constricted affect: check; hypervigilance: check; irritability: check. But is there impairment? The critical factor in many psychiatric diagnoses — distress or reduced ability to function. There is no easy answer.

PTSD is a well-established risk for Emergency Medicine (EM) providers from EMS to the trauma bay 1. In-hospital EM providers experience PTSD at more than double the rate of the general population, somewhere between 15 - 20% 2. Rates in first responders have been shown be as high as 40%. Evaluation of the DSM-5 criteria for PTSD begins with “exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence,” including “experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s) (eg, first responders collecting human remains; police officers repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse),” which clearly includes EM professionals 3. The diagnosis in this population is confounded by the stigma of perceived weakness, and the volume of trauma seen, i.e. which one was the precipitating cause.

EM residents experience PTSD at similar rates as the EM physician population 4. Changes to duty hours and time off policies have improved resident satisfaction while reducing stress and burn out 5. The focus on resident wellness includes training strategies for sleep, exercise, nutrition, health, work-life balance, mindfulness and positivity 6. These changes are critical to the long-term well-being of the profession; they may not be the only measures necessary.

In a paper in press in Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vanyo et al makes a comprehensive evaluation of PTSD in Emergency Medicine residents 7. They note overall improvement in resident well-being but found “no specific effort has yet been made to identify, prevent, and treat the emotional distress that results directly from repeatedly witnessing trauma among emergency medicine resident physicians.” In addition to the challenges of diagnosis, there is little evidence for effective methods of prevention.

When diagnostic criteria are clearly met for PTSD, there are treatment options supported by randomized controlled trials. Several categories of treatment include trauma-based cognitive behavioral therapy, debriefing (critical incidence stress debriefing), cognitive behavioral stress management, mindfulness-based stress reduction, autogenic training, and relaxation response training. There is a notable similarity between these methods and some generalized wellness practices. However, the authors caution against grouping wellness and PTSD together. Of these methods, trauma-based cognitive behavioral therapy reduced rates of PTSD to 9% compared to 42% with general counseling 8, thus highlighting the need for specialized treatment. Interestingly, the authors noted that mindfulness, which is increasingly a component of wellness programs, has been shown to be particularly effective in studies of PTSD in the military, who are similarly stoic like in-hospital EM providers.

Exposure to trauma in the Emergency Department provides the textbook environment for the development of PTSD. Most in-hospital EM physicians begin experiencing trauma on a regular basis during residency, which is already a time of heightened stress. Residency wellness programs are effective at reducing the negative impacts of generalized stress, but should improve mechanisms for the detection and treatment of PTSD before distress becomes impairment. Additional research is needed on prevention, especially in the resident population.

References

- Lum G, Goldberg RM, Mallon WK, Lew B, Margulies J. A survey of wellness issues in emergency medicine (Part 2). Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:242-8.

- Luftman K, Aydelotte J, Rix K, et al. PTSD in those who care for the injured. Injury 2017;48:293-6.

- Pai A, Suris AM, North CS. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, Change, and Conceptual Considerations. Behav Sci (Basel) 2017;7.

- Mills LD, Mills TJ. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among emergency medicine residents. J Emerg Med 2005;28:1-4.

- Choi D, Cedfeldt A, Flores C, Irish K, Brunett P, Girard D. Resident wellness: institutional trends over 10 years since 2003. Adv Med Educ Pract 2017;8:513-23.

- Ross S, Liu EL, Rose C, Chou A, Battaglioli N. Strategies to Enhance Wellness in Emergency Medicine Residency Training Programs. Ann Emerg Med 2017.

- Vanyo L, Sorge R, Chen A, Lakoff D. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Emergency Medicine Residents. Ann Emerg Med 2017.

- Ponniah K, Hollon SD. Empirically supported psychological treatments for adult acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: a review. Depress Anxiety 2009;26:1086-109.

James Spearman is a fourth year medical student at the Medical University of South Carolina.