Rose Kleiman

June 26, 2017

Is the emergency department (ED) the right place to inquire about a patient’s sexual orientation? A recent study published in JAMA Internal Medicine points toward yes[i].

While lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) populations often report poorer health and less access to health insurance and health services, lack of data on sexual orientation is a barrier to understanding and addressing these disparities. Recent efforts to capture data on sexual orientation have been made by both the US Department of Health and Human Services and the National Academy of Medicine. Yet, few health systems or emergency departments (EDs) regularly collect data on sexual orientation.

Researchers for the Emergency Department Query for Patient-Centered Approaches to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (EQUALITY) Study used a mixed-methods approach to try and understand the willingness of patients to disclose and of providers to collect information on sexual orientation in the ED. The research team conducted in-depth interviews with patients and ED professionals in the Baltimore, Maryland, and Washington, DC, areas and used results from the first, qualitative phase to develop a national survey of patients and ED providers.

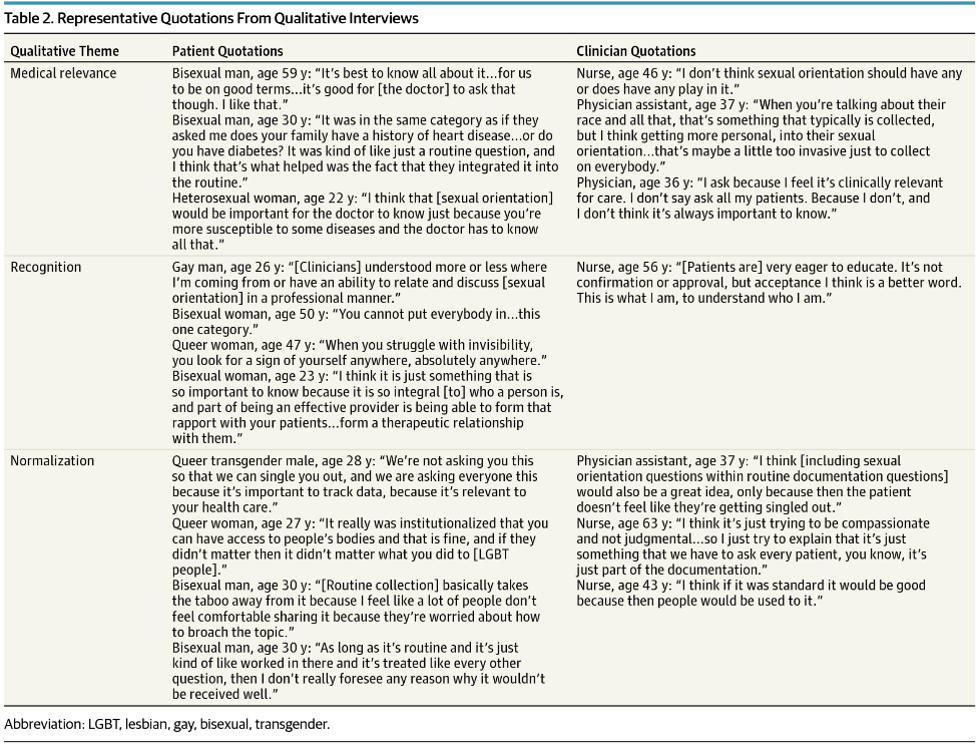

Findings from their qualitative interviews (see Table 2 below) highlight the following themes when discussing routine collection of sexual orientation in the ED: Medical relevance, normalization, and recognition.

The qualitative interviews describe the disconnect between patients and providers. Emergency providers felt if sexual orientation was not relevant for a patient’s immediate care plan, it was not necessary to know and thus not important to ask. Patients felt that their sexual orientation was essential information for their overall health and wellness, similar to inquiring about family history of heart disease or exercise habits, and thus should be a routine part of screening. Therefore, the lack of screening on sexual orientation may be a missed-opportunity for providers to build meaningful relationships with patients.

Similar findings were reflected in the quantitative results from the national survey. A total of 80% of emergency providers reported they thought patients would be offended if asked their sexual orientation in the ED, with 78% believing patients would refuse to provide this information. By contrast, only 10% of patients reported they would refuse to provide such information in the ED and only 11% reported that they would be offended if sexual orientation data were routinely collected.

Patients in the survey also emphasized the importance of collecting data on sexual orientation for recognition and normalization of LGBTQ individuals in society. It was expressed that standardizing the collection of this information may help to further promote patient-centered care for all patients.

The research team found that the preferred method of both patients and clinicians for collecting this information was through a nonverbal self-report. The EQUALITY team currently has a trial under way to study the different ways of collecting this information to determine the optimal method.

This study does have some limitations. First, the qualitative interviews were only sampled from one region of the United States; however, the interviews informed the development of the survey, which found similar themes on a national level. In addition, the study did not test how patients actually respond when asked about sexual orientation information in a clinical setting.

While this article highlights the significance of collecting data on sexual orientation, it leads to an important message for emergency providers: patients believe that their sexual orientation is an important component of their overall health and feel that it is necessary information for their providers to know. Whether it is essential to determining an immediate treatment plan or not, querying about a person’s sexual orientation can lead to a more person-centered approach to care.

[i] Haider, Adil H., et al. "Emergency Department Query for Patient-Centered Approaches to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity: The EQUALITY Study." JAMA Internal Medicine (2017).

Rose Kleiman is a medical student at the GW School of Medicine & Health Sciences

.png)

.jpg)