With an estimated 27,000 foreign fighters joining the Islamic State and its cause, one can’t help but wonder: what is the driving force behind the support? This article aims to provide an answer, as well as a solution to the underlying problem.

What is ISIS?

For those who are unfamiliar with the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), its major debut happened in 2014, when the Islamic State successfully captured key Iraqi cities, defeated Iraqi government forces, and proclaimed itself as a worldwide Caliphate. Ever since then, there has been a massive push by the Islamic State towards its ultimate goal – the apocalypse.

Contrary to popular belief, ISIS follows a strict medieval form of Islam , which is why it practices very extreme war tactics like crucifixions, beheadings, and slavery. In the Islamic State’s interpretation of the Koran, the apocalypse will bring an end of the world. The prophesy also reads that a reestablished God’s Kingdom on Earth, the Caliphate, will fight a decisive battle at Dabiq against the infidels, where Jesus will join the Caliphate and end the war.

While most ISIS recruits come from the immediate territories captured by ISIS, i.e. Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State has a very sophisticated recruitment system in place that draws supporters from around the world.

Recruitment Methods

Islamic State uses sophisticated propaganda tactics to persuade potential recruits and promote their cause. ISIS targets specific groups of people and uses tailored media for different parts of the world. Dabiq, now Rumiyah, is a magazine in English, which caters to English speaking audience, while Dar Al-Islam does the same for French speakers, and Istok for Russian speakers. By diversifying its media, ISIS can influence its targets with regionally-relevant propaganda, which has stronger effect then general propaganda does.

From propaganda videos, to infographics, to extensive social media campaigns, and even a news channel – every piece of propaganda ISIS creates is top quality. By creating visually appealing propaganda that reflects popular media – like video games, TV shows, and pop culture – ISIS is reaching a wide audience and successfully communicating its ideas in a very powerful way.

ISIS associates terrorism with positive ideas and thoughts, and in its methods, uses terror to seduce, not terrorize. Since modern age audience is so susceptible to action and violence, it’s also susceptible to Islamic State’s media.

Vulnerability

Now, why does the Islamic State make such a great effort to target Muslims across the globe? Short answer: it is easy to influence people who do not feel accepted in society.

You see, Islamic terrorism is all about polarization.

In its propaganda campaigns, the Islamic State targets minority Muslims, who have been oppressed by society. That is also the reason regionally-catered propaganda is so effective.

https://akirk.carto.com/viz/9694dcca-353e-11e5-8d22-0e0c41326911/embed_map

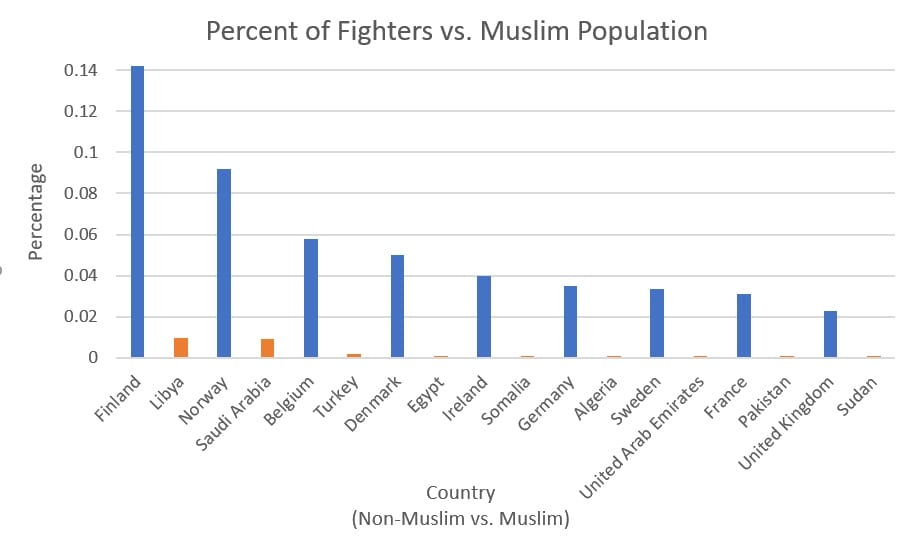

The map above shows estimated statistics on foreign recruits who had joined the Islamic State. By using that data, the percentage of recruits who joined ISIS out of total Muslim population can be derived.

As it is evident from the graph, it is striking that it is countries with a minority Muslim population that have the greatest percentage of fighters joining the Islamic State. This is caused by the pressure the society puts on Muslims. By alienating the Muslim population in Muslim minority countries, great tension is created. Muslims do not feel welcome, feel underrepresented, discriminated against, and seek ways to be recognized. ISIS propaganda acts on those vulnerabilities making people believe in an ideal society, where they feel welcome and valued.

On the other hand, there is a much lower percentage of Muslims joining the Islamic State from Muslim majority countries. Again, same principles are applied here: Muslims do not feel alienated, undervalued, or underrepresented. They have a voice in their government, are involved in political, social, or even their own radical groups. There is no reason for them to join ISIS unless they truly believe in the cause.

The Islamic State propaganda targets Muslims who lack a sense of unity, and the statistics prove that ISIS tactics are working.

Residents of Iraq and Syria are a bit of a different story, since they felt oppressed by their governments and ISIS promised to raise their quality of life. Since Iraq and Syria are zones of current conflict, it’s much more difficult to gauge residents’ reasons for joining the Islamic State, but judging by the sheer number of refugees fleeing from those countries, it is easy to say that ISIS is not that popular in Iraq and Syria.

Solution

To undermine ISIS recruitment efforts, Muslims, overall, need to be treated fairly. If Muslim minorities got the treatment they deserve, there would be no need for violence and extremism. By creating anti-Muslim policies and by alienating the religion, radical responses are created.

By incorporating Muslims into society through public office, cultural exchange programs, clubs, and sports teams, the sense of undervalue decreases. People who once were angry with the way Muslims were treated, felt alone, or felt segregated against, will have less of a need to join a radical organization – they will feel like their voice is finally heard.

Speaking of being heard, instead of shunning away refugees, give them a voice and safety they try to obtain. If refugees share their first-hand experiences with the Caliphate and with ISIS, many will realize how different the reality is from an image ISIS is trying to sell.

Caveat: The views expressed in this blog are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or the George Washington University.