By Grace Martinez, Masters in Media and Strategic Communication ‘23

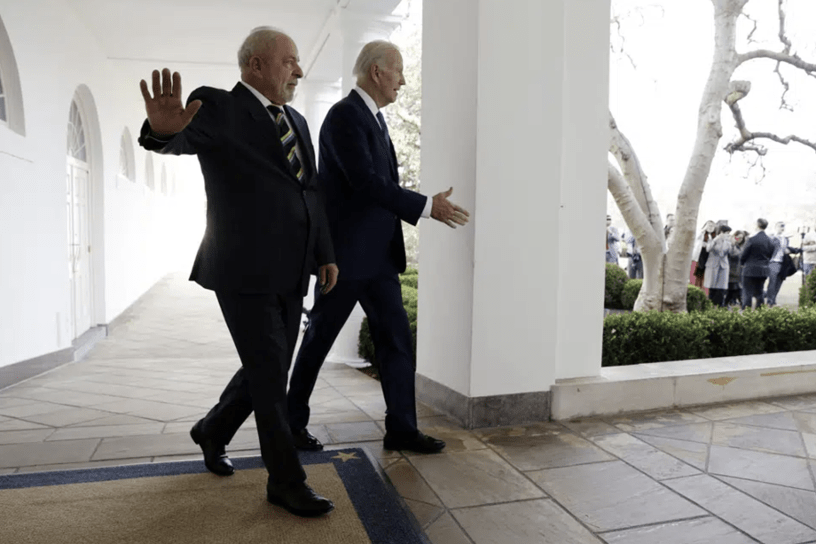

meeting at the White House in Washington, D.C. (Jonathan Ernst/Pool via AP)

On Friday, February 10th — Brazil’s newly elected president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, met with President Joe Biden at the White House in Washington, D.C. The two heads of state spoke of the multilateral relations between the two countries and of their shared interests as the ‘largest democracies in the Western Hemisphere’. The story sold to the public was one of partnership and prosperity, and the presidents spoke of their joint plans for peace, security, and respect. And the visit was a success. Namely for one individual in particular: Brazilian President Lula da Silva.

Now in his third term as president (first in-office 2003–2010), President Lula da Silva has a clear vision for Brazil; as a new world order emerges, Brazil is positioning itself to be seen as an emerging global power. The country views itself as a representative at-large for developing countries—also, a diplomatic leader, defender of multilateralism, and friend to all.

In a speech Lula da Silva gave at the World Economic Forum (2010)[1], he outlined the country’s vision:

“I have lately seen many international publications say that Brazil is fashionable nowadays. Allow me to say that, although that is a kind expression, it is not appropriate. Fashions are fleeting, ephemeral things. Brazil wishes to be and will be a permanent player in the new world scene. Brazil, however, does not wish to be a new force in an old world. The Brazilian voice wants to announce, loud and clear, that a new world can be built. Brazil wishes to aid in the construction of this new world…”

The bolded sentences above represent Brazil’s narrative, and how they view themselves fitting into the new world order. So, for Brazil the meeting at the White House was a major step toward achieving its two main goals of creating a new, widely accepted identity abroad and having a greater role to play in shaping the future world order. So, why is the country’s path forward still so complicated?

Contradicting Motives

Brazil views its narrative as being dependent on idea that they are a friend to all. To be seen as a diplomatic leader, emerging power, and as a country with international influence, a close relationship with the United States is critical. But alternatively, Brazil wants the freedom to pursue its own interests even as they interfere in the country’s relationships with countries located in North American and Europe. Brazil’s actions take on a narrative of their own, one that contradicts the idea that they are friendly with everyone. This is exemplified by Brazil’s close alliances with both the United States and Iran.

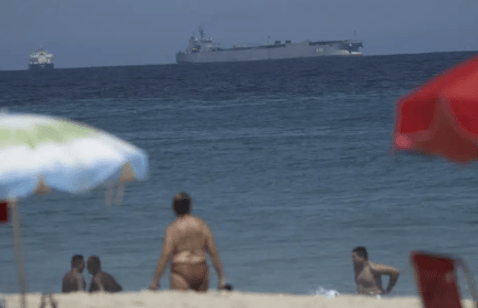

Earlier this year, Brazil’s personal interests were put on display when the country allowed the Iranian warship, IRIS Makran, to dock in their waters’. Brazil ignored requests from the United States and several other western countries to block the presence of the Iranian warship in the Western Hemisphere, with these countries citing that it granted their unfriendly military a strategic foothold.

Photo caption: Iranian warship, IRIS Makran, docked off the Brazilian coast (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

For Brazil, a close relationship with Iran is viewed as a way to help developing countries in Africa and the Middle East. President Lula da Silva has placed a high value on the partnership between the two countries because Iran helps Brazil to identify as a representative at-large for developing countries and showcases the economic and political influence they have globally.

The way Brazil’s narrative creates conflicting relationships with such as the U.S. causes confusion and unnecessarily puts the country’s motives into question. This flaw is detrimental to the overall goals of the country, instead of building trust and showcasing power, the convergence of values makes Brazil look ineffectual and untrustworthy.

Moving Forward

At this moment, Brazil’s is focused on becoming a permanent player in the new world order and acting as a pseudo representative-at-large for developing countries. The country’s identity narrative is that they are a friend to all, but its long been observed that rising powers are often in conflict with existing ones – as is exemplified by the tensions between U.S. and Brazil regarding Iran.

Brazil find itself in a grey area between where they want to be and where they are. When you are working to gain power it is important to have alliances everywhere, but as you take on a new identity in the new world order conflict will rise – often surrounding the decisions you have to make. Brazil is still able to relate to its old identity while pushing for others to accept its new one but for how long and at what cost. In the end, the country’s growing list of contradictions will harm its narrative.

Here is the full report.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. They do not express the views of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or the George Washington University.

[1] Speech by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva at the World Economic Forum – Davos, January 29th, 2010. Ministério das Relações Exteriores. (n.d.).