Voyaging Toward Global Connection

Three George Washington University juniors have been named recipients of the prestigious 2025–2027 Obama-Chesky Voyager Scholarship for Public Service. Eve Danishevsky, Malyna Gomez Trujillo, and Amanda Valenzuela were selected for their commitment to public service, community engagement, and demonstrated leadership potential.

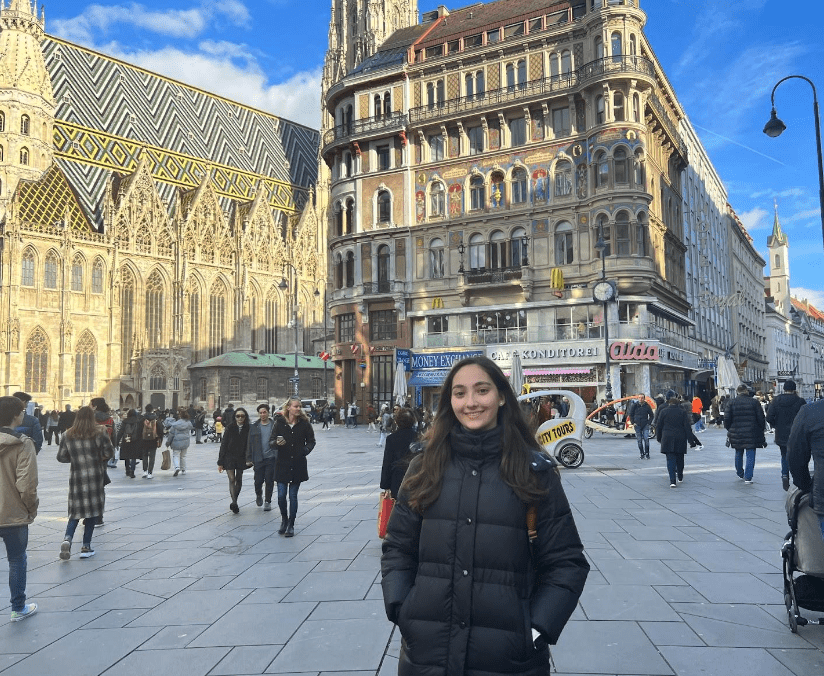

We recently caught up with Eve, who, in addition to her studies as an Elliott undergraduate student pursuing a B.S. in International Affairs and Finance, is a Dean’s Scholar and a program coordinator of Elliott School’s Central Asia Program. We spoke with her about plans to translate her experiences into values-based leadership that inspires equitable and lasting change.

Q1: The Voyager Scholarship is all about building bridges and gaining empathy through new experiences. How do you think traveling and meeting new communities will change the way you approach public service?

One of the most unique parts of this scholarship is the $10,000 allotment for a summer travel opportunity, which I plan to use for on-the-ground research across all of Central Asia. International development is a broad category of public service that I chose as my focus area in my application, and I hope to hone in more narrowly on the powerful ways that intercultural immersion can serve as a form of soft diplomacy. There are so many misconceptions about Americans and Central Asians from each respective region, and the opportunity to meet with a wide variety of different groups will give me the opportunity to gain nuanced insights into how different people understand identity and global citizenship. These are perspectives that I would never be able to fully grasp from a classroom or through research alone.

Q2: President Obama and Brian Chesky, who founded the scholarship along with Michelle Obama, talk a lot about curiosity—how it can open doors and create understanding. How has curiosity shaped your journey so far, and how do you hope to build on that through this program?

Curiosity is the reason that I chose GW, for the opportunity to continue expanding my worldview on parts of the world that aren’t particularly emphasized in typical international relations programs. That curiosity has made me realize that the change that I want to enact transcends the typical boundaries of what people think it means to work in public service—I want my work to connect people of different cultures in ways that are long-lasting and intergenerational. The funding and mentorship opportunities that this program provides will let me expand on that in ways that I can’t even imagine right now, whether that’s through collaborating with local leaders to create initiatives that foster mutual understanding or working more broadly with the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs to research more about the efficacy of free exchange programs in Eurasia.

Q3: The scholarship focuses on values-based leadership. What values are most important to you in your public service work, and how do you hope to grow as a leader over the next two years?

Community, impact, and commitment drive my work, and they have all guided me in my various roles on campus, from being a First Gen Mentor to a Peer Advisor to a Program Coordinator for our Central Asia Program. Over these next two years, I look forward to growing as a leader who can translate these qualities into quantifiable change, and I am already working with a coach who is helping me build on those values for my summer project. I am so excited to continue learning about the world around me and how values-based leadership can create equitable change.

Q4: Exposure to new places often changes how we see what’s possible. What’s one way you hope to take what you learn as a Voyager Scholar and bring it back to GW or your community?

I think that a deeper sense of global perspective and empathy can really transform how people think about leadership, especially at an internationally driven school like GW. As a Dean’s Scholar already researching Central Asian governance, the Voyager Scholarship will undoubtedly deepen my understanding of the institutions shaping this region and help me assess how intercultural initiatives influence capacity-building in those countries. But more than that, this program will show how people-to-people connections can serve as a powerful tool for the promotion of international engagement, and that is exactly what I want to bring back to my GW community. I hope that my selection for this scholarship proves that any passion project, no matter how niche or under-researched, has value that is waiting to be recognized.

Q5: This scholarship is about preparing the next generation of leaders. Looking ahead, how do you imagine using the network and resources you gain to make an impact?

I look forward to attending the annual Voyagers Fall Summit and meeting the rest of my cohort, as well as getting the chance to hear from experienced leaders in public service. As I prepare to enter a field as small as Central Asian Studies, being around people who are as interested in building bridges across different communities as I am will be crucial to refining how I turn ambitious concepts into tangible actions.

About the scholarship: The Voyager scholarship was created by former President Barack Obama, former First Lady Michelle Obama and Airbnb co-founder Brian Chesky. It provides financial aid, summer travel opportunities to broaden recipients’ exposure to new communities and cultures, and access to a network of mentors and leaders in public service. This year’s cohort includes 100 students from 71 colleges and universities across 34 states and United States territories.