When I learned that I would be an Asian Field Research Fellow with the Sigur Center for Summer 2019, I was elated for many reasons; one of those reasons was tied to my own personal upbringing. For decades, members of my family have volunteered to support the Santal tribe in Birbhum district, West Bengal. The Santal are an indigenous group (characterized in India as adivasi) with a large presence in the country’s eastern states. I’ve visited programs serving the Santal people since I was a little girl; some of these programs include an academic program to prepare children for admissions to Bangla-medium formal schools, and vocational programs for adults to train in various occupations, such as beautician and electrician work. These programs were aimed at diversifying economic opportunity for the Santal people who have typically been involved in agricultural labor in the mainstream economy. Previously Santal children had not enrolled in large numbers in West Bengal’s mainstream schools for various reasons, such as language barriers and family obligations. I’ve seen Santal children and youth benefiting from these programs to gain more economic stability and also attain formal schooling, with members of this community increasingly pursuing secondary school completion and higher education. Santal individuals are now involved in running these programs as well. As I learned more about access and empowerment, I began to wonder about the best ways to enhance existing programs and services for the Santal community as they continue to integrate with mainstream society while maintaining the cultural values and traditions of their tribe. This question stayed with me throughout my work experiences and studies in education in the United States and on a couple of international education projects, and throughout my studiesat GW in international education including on indigenous populations. Receiving this fellowship meant I had an opportunity to delve further into understanding the current needs of the Santal community. In this post, I will discuss past experiences with the Santal people, and introduce the research I am conducting involving both Santal women in Birbhum and urban women in Kolkata.

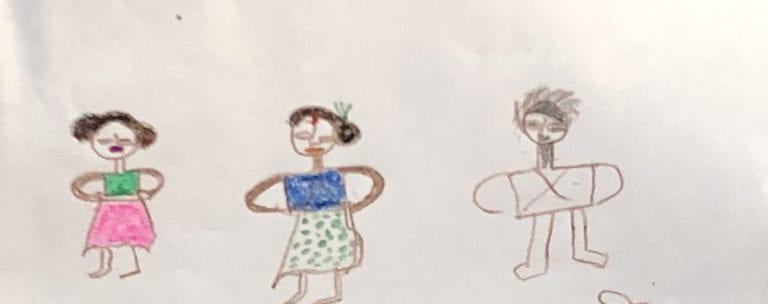

I am not an expert in Santal culture, but personal experiences with the Santal tribe from childhood taught me to appreciate their beautiful ways of respecting nature and their greater kin. I have seen their customary song and enej performances on many occasions, with the women gracefully holding hands and dancing in a line while wearing matching sarees and flowers in their hair, and the men playing the dhol and showing their warrior dance in a captivating display of strength. I’ve seen the intricate tattoo designs that the Santal people wear, some on their arms and some at the base of their neck for example. I’ve visited their homes, generally constructed of mud and incorporating domestic engineering, such as kilns built into floors. I’ve also attended a religious ceremony of theirs held in a neighborhood forest, occurring in parallel with Diwali/Kali Puja. In addition to seeing their long-established ways of life, I have seen their steps taken towards participating more in mainstream education and economic systems. One particular memory I have of visiting the academic preparatory program as a child was seeing another small, chubby-faced Santal child receiving some writing utensils, examining them with detail, and delicately placing the utensils into her pencil case, and then into her bookbag. My father commented to me how the Santal people, conventionally minimalist, showed great appreciation and care for whatever material goods they did have. Little did I know then that I would one day be speaking to some of the children in that class as adults, asking them about their own experiences raising their children! Yet that is exactly what happened a couple of weeks ago in Birbhum; it was the only place where I could immediately identify some faces that are now grown women and where I was called by my daak naam (family nickname) instead of my good name.

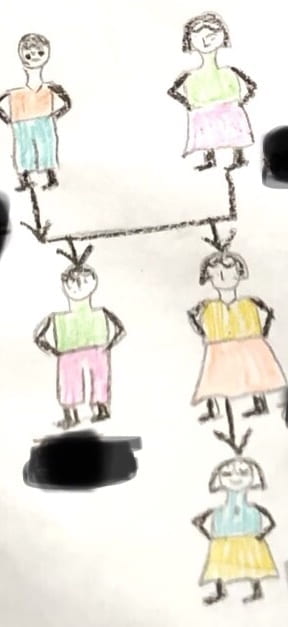

For my capstone project, I am seeking to learn more about mothers’ and grandmothers’ perceptions of early childhood development in West Bengal, specifically focusing on the contexts of Kolkata and Birbhum districts. In addition to speaking with Santal mothers and grandmothers, I also spoke to mothers and grandmothers who receive nonprofit services in Kolkata; I will write more about my experiences with them in a follow-up blog post. Early childhood is a wide-ranging field with key priority areas for raising young children as reflected by the World Health Organization’s Nurturing Care Framework – good health, adequate nutrition, opportunities for early learning, security and safety, and responsive care-giving. The practice of asking mothers about their child-rearing practices has been cemented on an international scale through data collection initiatives, such as the UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster (MICS) Surveys. My open-ended interviews with mothers and grandmothers were influenced both by the Nurturing Care Framework and the MICS Surveys, plus my own interests on inter-generational perspectives on early childhood and play-based learning. Hearing the Santal women’s perspectives on early childhood with these questions as guides was a unique opportunity for me to learn how this Santal community in Birbhum district has adjusted to socio-cultural and economic changes around them – not only in the state of West Bengal but in India overall, as well.

At this particular site, Santal mothers and grandmothers whose young children/grandchildren attend the academic preparatory program were interviewed. The group I spoke with included a combination of women who had themselves attended the program as children and those who had not. There was also a combination of women who had completed secondary schooling and those who had not. The women I interviewed were very confident in discussing their involvement, concerns, and hopes in raising their children. While I am currently in the process of analyzing the data in-depth, a few takeaways have stuck with me so far from the interviews:

I should note that this group represents a smaller sample from the larger Santal population in the area; my study is more exploratory in nature, but more investigation could also compare this particular Santal community to other Santal communities in the eastern region of India or compare the views of families from this program to other families participating in different programs serving the local Santal tribe.

A final topic that was discussed with the Santal women was the need to be “modern” – this was the exact word they used – and increasingly participate in the world beyond their tribal community, while still maintaining their language, culture, and values. Some women discussed always feeling “Santal on the inside”, whether they were working at an office that primarily conducts work in Bangla or at home in their village speaking in Santali. One mother noted that some members of their tribal community believe that they need to distance themselves from their Santal culture in order to be accepted by the majority population; however she herself did not agree that this notion was accurate. In fact, the majority of mothers felt that it was possible to be both Santal and a member of the mainstream society and economy in West Bengal. The women did agree that it was up to the Santal families themselves and no one else to ensure that their culture and norms would be taught to their children and future generations. These positive reflections on preserving culture and also knowing that a Santal woman now directs the program did cause me to consider the importance of community engagement and cultural understanding to the success of programs and services. When asked if they thought their children will stay in Birbhum district or go to other places when they grow up, the women laughed and concurred that their children were too young now to know what course their lives will take. One woman did remark that generally members of their community who left to go to other places would often visit frequently or move back after some time, finding comfort in familiar places, people, and songs. In some way, getting to visit the Santal academic preparatory program and speak with affiliated families on their hopes and dreams for their young children was for me a form of finding comfort in a familiar place.