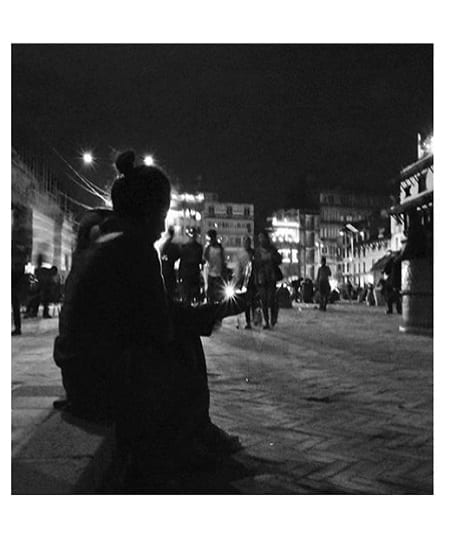

If you’re anything like me, you’re passionate about improving public health to a fault. Whether it’s reducing smoking among adolescents in the United States, preventing anemia among women of reproductive age in India or understanding the scope of technology-enabled projects in Nepal, you’re all in. All in your textbooks that is… until this summer. In my years of professional public health work, I had not yet had the opportunity to go out in the field and get my hands public health field work dirty! Talking to my friends who had done so was contagious so to speak. All puns intended, of course.

When I found a grant opportunity to conduct field work in Asia this summer, I was beyond ecstatic. I quickly put together a proposal and submitted it hoping for the best and I got it! As a female public health researcher semi-successfully adulting her way through life and graduate school, my self-confidence was at a peak when embarking on this journey. I had completed a desk review working with my collaborators for over a year. I knew the technical and non-technical factors associated with my field work. I had a good sense of the landscape and who I would be requesting key informant interviews from once we hit the ground running. I could read and write the local language, had friends and family in the area, and knew the city well. What could really go wrong I thought? Well plenty, it turns out so listen up and read closely so you can learn from my moments of “could have done things better”:

Lesson # 1: Your work begins long before you get to the field

Every country has a local ethical board who will want to know what type of research you’re conducting in their country, how, and what your plans are in collecting and analyzing the data you collect from their citizens at a bare minimum. Often, these ethical review applications are extensive in nature as they should be to protect citizens from harmful and unethical research practices. Bottom line is, you must build these applications into your overall timeline and get them in motion well before you plan to be on the ground. In my case, it took a full six months between pulling the application together, getting it reviewed, revised then finally approved. I did my homework by talking to others who had applied for local ethical approval to conduct field research in Nepal. They shared their knowledge which helped me understand the process a little bit better before getting started. I had individuals review my application before I submitted to catch any errors I might not as a total newbie in this aspect. Once I finally got the application submitted, I began building a relationship with the appointed point of contact. She was super helpful and open to me calling her directly for questions or a conversation. I wasn’t shy about reaching out to her for help and to keep reminding her every so often that my application was still pending approval. Thanks to her help and to all those who helped me along the way I was able to get approval in time for my summer field research grant!

If you walk away with anything from my observations here, remember this:

- Apply for local ethical approval well in advance. Give yourself say 6 months or longer to be on the safe side.

- Talk to others who’ve applied for ethical approval before and learn from them.

- Have others review your application to catch any errors before you submit.

- Build a relationship with your point of contact overseeing your application and maintain it after you gain approval.

Lesson # 2: You must be culturally responsive but darn it sometimes it’s really oh so hard I tell ya

When the experienced and the wise tell you being culturally responsive is a must in your classrooms, they weren’t kidding, ya’ll! Working in Nepal was no different. I had a list of people I had reached out and the rate of response was fantastic thankfully. However, I quickly realized that most individuals preferred a follow-up phone call to chit-chat and get to know you better prior to committing a day and time for an interview. Getting them on the phone wasn’t easy either. Often, you’d have to try more than once, exercise those patience muscles and keep yourself busy. When you finally nail down a day and time, then be prepared to wait because 9AM might mean 10AM really for some individuals and that’s just how it works in Nepal. Some of your key informants maybe so busy they have three individuals down for the same time. What this means is you find yourself asking them for a time where only you can meet with them and have their attention for say 30 minutes to an hour. I realize I come off somewhat sarcastic. I promise that isn’t my only goal here. It can get frustrating especially on days when you have multiple interviews with a small margin of time to travel across town for the other interviews. In the same breath though sometimes, this worked to my favor. The flexibility in time and scheduling meant I was able to reschedule with some individuals when it just was not possible to make it to my appointment. I was amazed by how easy it was to do this and thankful for their generosity in fitting me in another day and time. There was reciprocity involved in this laidback approach! I realized that although people weren’t bound to agreed upon timetables and sure that pushed me out of my comfort zone, it also made me appreciate the lack of “time consciousness” rigidity. Is it fun to have to wait an hour to hour and a half for an interview you scheduled? NO, not at all, never. However, there is still a beauty in going with the flow and realizing that this is how things work in Nepal and that’s okay! Accepting that I can’t change the working culture in Nepal, I decide to roll with it and mentally prepared to accept scheduling fluidity. C’est la vie!

Tips and tricks for responding to the working culture in Nepal:

- Phone calls and in-person meetings are preferred over emails and video calls for work-related conversations.

- Schedules are fluid so learn to go with the flow.

- Have a good book to read or an electrifying Spotify playlist to carry you through time spent waiting.

Lesson # 3: Young and female ≠ professional, leader or an expert. What gives?!

Where I really could not find myself going with the flow is when I it dawned on that gender bias still exists and you just must deal with it. Here are some of my interactions while interviewing key informants or discussing my field work with others:

Ichhya, you’re so young (and female). No one will take you seriously in Nepal. Ask falano… they’ll tell you how it is…

So, you’re a master’s student huh?

Are you married? Do you have family in America?

What is your father’s name? Where is your home again?

I noticed your last name is Pant. Which part of the country did your ancestors come from?

Do you have a greencard or US citizenship? (aka what is your immigration status?)

Are you related to falano (Nepali slang for saying “so and so”? You know falano families and Pant families tend to marry each other… Since they are involved in this project too, I wondered if ya’ll were related, you know how it goes…

Notice any trends here? I was shocked I tell you (not really) that I was on the receiving end of such gendered mindsets. Okay, so I can accept that I may look young and I’m female. I get it. It’s a man’s world they say. Especially in Nepal. Still, the assumption that I am master’s student was an intriguing gender bias that was persistent across many interviews. What I’m unsure of is whether it is because I look young or if I’m a female. Probably an interaction of the two factors. What’s important is that someone like me isn’t associated with leadership, expertise or doctoral work. Of course, the sample size here is a meager one but I hope other women working in public health in Nepal speak up with their experiences in the field to balance out this conversation.

In America, we note how public health is a woman’s profession. It doesn’t feel that way in Nepal. Where are the women working in the field there I thought to myself? My sample consisted of 80% males. Do women make it to leadership positions in the field of public health in Nepal? Am I just not meeting them? In talking about this with a highly qualified public health female professional working in Nepal, she confirmed that it’s just the norm. People seem to somehow miss the “PhD” behind your name and refer to you as baini (little sister) instead of “Dr. falano”. They openly take pity on you if you aren’t married by X age or have children. You are defined by who your parents are, what caste you belong to, who your ancestors were, and whether you have a husband or children. It’s just how it goes for the most part. Imagine having to navigate a working environment where you’re baini and your male counterparts are “Dr. falano” after years of hard work and earning a PhD behind your name from a globally recognized public health institution. Unpleasant and frustrating, to say the least…

Not everyone adopts and subscribes to such a viewpoint of course and there are teams and environments where such experiences aren’t the norm. My intention here isn’t to generalize but to start a conversation. Can young and female become normatively accepted as the face of public health leadership in Nepal? If so, what will it take and when will it happen exactly? Yes, I know what you’re thinking. It is 2018 and we’re three months away from 2019. What gives?!

If you’re curious and still with me, here’s how I responded to the questions I noted above:

Ichhya, you’re so young (and female). No one will take you seriously in Nepal. Ask falano… they’ll tell you…

- (Seriously taken aback)… really? I guess I will have to rely on my intellect and present myself accordingly, so I am taken seriously… (still taken aback….)

So, you’re a master’s student huh?

- Oh no, I’m a third-year doctoral student. I mentioned that in our previous conversations but perhaps you missed it. I got my master’s six years ago in fact.

Are you married? Do you have family in America?

- Yes, I do have family in America but here in Nepal as well.

What is your father’s name? Where is your home again?

- My home is in Kamalpokhari. Do you know Kumari Hall? Within walking distance to it, in fact…

I noticed your last name is Pant. Which part of the country did your ancestors come from?

- (extremely uncomfortable) I consider myself “duniya ko Pant” (Pant of the earth)… followed by awkward laughter…

Do you have a greencard or US citizenship? (aka what is your immigration status?)

- (extremely uncomfortable) Umm… I am a Nepali citizen… (still extremely uncomfortable)

Are you related to falano (Nepali slang for saying “so and so”? You know falano families and Pant families tend to marry each other…

- No, I had no idea that these families marry into each other. We aren’t related though. (awkward silence)

I don’t know if my response does justice to balancing tilted gender perspectives or if a key informant interview is where I should even attempt to doing so. I frankly was ill-prepared to address them. I did the best I could in the moment where these questions or comments came my way. I realize there are larger gender norms at play and my experiences aren’t simply an artifact of viewpoints in the public health corner of Nepal. We can’t change them overnight of course but I feel, strongly might I add, that it’s time we begin to talk about them, address them and intervene wherever and whenever we can. So, at the risk of appearing naïve and controversial, where do we begin? I want to especially hear from my female and young or (not) public health and development professionals in the field. Please speak up about your thoughts and experiences on this matter because #Timesup.

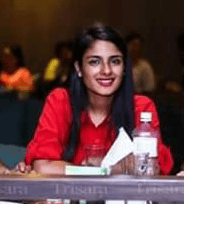

Ichhya Pant works at the intersection health, evaluation, data and information and communication technologies (ICTs) with a focus on vulnerable population such as immigrants, refugees, women and children. Currently, she serves as a Research Scientist focusing on monitoring and evaluation on the RANI Project which aims to test whether a multi-level social norms based intervention will reduce anemia in women of reproductive age in Odisha, India.

Ichhya Pant works at the intersection health, evaluation, data and information and communication technologies (ICTs) with a focus on vulnerable population such as immigrants, refugees, women and children. Currently, she serves as a Research Scientist focusing on monitoring and evaluation on the RANI Project which aims to test whether a multi-level social norms based intervention will reduce anemia in women of reproductive age in Odisha, India.