Religion as a driver of conflict

Religion is often seen as a key cause of conflict, both in individual

societies and on the international scene. While the proponents of this

viewpoint are numerous, one scholarly figure ought to be remembered

as the central point of reference for this argument. Samuel Huntington

(1993; 1997), borrowing partly on an idea put forward by British-American

historian, Bernard Lewis (1990), became the most prominent voice

claiming that religious and cultural identities would be the main driver

of international conflict in the new world order following the end of the

Cold War. He argued that although the nation state would remain the

most powerful actor in the international arena, the ‘clash of civilizations’

would become the new force fueling conflict. His categorization of the

world into nine different civilizations is based mostly along religious

lines. He contends that conflicts can occur both on a local level within

a state with groups belonging to different civilizations, or among neighboring

states (‘fault-line conflicts’); and also on a global level between

and among states that belong to different civilizations (‘core-state conflicts’).

He argues that civilizations compete on the international scene,

and that this competition can turn into violent conflict, most importantly

because of the different religions that have formed these civilizations.

Conflict lines on the international scene, he maintains, are primarily

those between the Muslim and the non-Muslim world, which have

shaped the history of conflict for centuries (Huntington 1993, 1997).

Religion as a Mediating Factor

Besides examining religion as a driver of violent conflict, scholars have

also been concerned with the extent to which religion may indirectly

foster or tolerate violence. The nexus between faith and conflict is

thus addressed by referring to religion as a cause of structural violence

through discrimination and exclusions. This line of reasoning is supported

by the fact that religious identities can erect potent boundaries

and provoke fierce confrontation within a group when there is excessive

emphasis on claims by some that they belong and adhere to or

are protecting a set of absolute truths. Anthropologists often examine

how, within and across societies, religion is used to create differences

among people. Political scientists argue that religion, through its

inherent distinction between an in-group and an out-group, can lead to

structural violence both within societies and on the international scene.

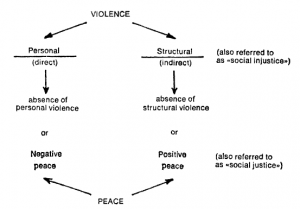

Urging that we take into consideration the existence of various levels

of violence, Galtung (1969) argues that religion is often the source of

‘cultural violence’, a form of violence that is used to legitimise other

forms of violence. Without seeking to establish a direct cause and effect

between religion and violence, Galtung shows how different factors

such as religion, ideology, language and ethnicity become intertwined

to shape ways of thinking and behaviours that can lead to situations of

exclusion, discrimination and eventually also physical violence.

Another way of establishing an indirect relationship between religion

and violence is by focusing on the inaction of religious groups. Boulding

(1986), for example, argues that religions have not succeeded in using

their potential for peacebuilding, and thus they have lent support to

states when they are at war. While religion has not ignited a conflict,

it has worked as ‘an obstacle to peace’.

The majority of experts on religion and politics, nationalism, and conflict

and peace, however, concur that conflicts are usually characterised

by a set of motivations and their interactions, and thus an analysis of

conflict factors cannot be limited to only one of these dimensions, be

it religious, political, historical, or economic (see, for example, Berdal

2003, 492; Laitin 2007; Mayall 1990; Toft 2007).

The Iraqi-born British historian Elie Kedourie (1960) became famous

for his controversial view of nationalism as a Western invention. He

regarded nationalism as the greatest evil of the twentieth century, the

export of which was particularly catastrophic in the Middle East. While

likening nationalism to religion because of its despotic and divisive qualities,

Kedourie did not, however, attribute the emergence of nationalism

to religion; indeed he regarded the two as being essentially opposed.

Scholars with expertise on the Indian subcontinent (among them: Talbot

2007; Bhatt 2001; Mayall and Srinivasan 2009; Waseem 2010) argue for

more nuanced readings of the apparent inter- and intra-state religious

conflicts affecting India and Pakistan. This means examining central

elements in the emergence of violent attacks on religious minorities

and on sacred sites. Among those are the historical legacy (from both

during and before the colonial era), attempts to elaborate modern

(secular) nationalist projects, weak state institutions, and blatant

competition for political power among and within ethnic groups and

competing religious and political leaders. It is against the background

of these factors and in the changing context as societies feel the

pressures of modernity, globalisation and multicultural society, that

violence becomes morally and religiously sanctioned, argues Indian

psychoanalyst Sundhir Kakar (1996).

Taking into account economic factors, a global study coordinated by

Oxford professor Frances Stewart (2008) reaches similar conclusions.

It centres on the hypothesis that violent conflict in multicultural

societies occurs in the presence of major horizontal inequalities among

culturally defined groups. The argument is that when cultural differences

coincide with economic and political differences between groups, this

can cause deep resentment that may in turn lead to violent struggles.

This builds on the work of Gurr (1993) and Collier et al. (2003), whose

theories stress the centrality of mobilisation based on group identity and

poverty and deprivation in conflict. It also confirms the finding by Fearon

and Laitin (1996) that multicultural societies do not generate conflict just

because they are multicultural. It is rather the combination of multiple

factors that ignites conflicts.

Wolff (2006) proposes comprehensive elaboration on these factors.

He usefully distinguishes between ‘underlying’ (structural, political,

economic, social, cultural, perceptual) and ‘proximate’ causes of conflict

(i.e. the role of leaders and their strategic choices, both domestically

and in neighbouring countries). Underlying causes are ‘necessary, but

not sufficient conditions for the outbreak of inter-ethnic violence’ (Wolff

2006, 68). The ‘proximate’ causes, by contrast, enable or accelerate

conflicts in situations ‘in which all or some of the underlying “ingredients”

are present’ (Wolff 2006, 70–71). Accepting the existence of this

multiplicity of factors leading to multiple configurations thus explains

‘why, despite similar basic conditions, not every situation of ethnic tensions

leads to full-scale civil war’ (Wolff 2006, 71). Ethnic conflicts, Wolff

argues, are not necessarily always about ethnicity; rather, this is often

‘a convenient common denominator to organize a conflict group in the

struggle over resources, land, or power […] a convenient mechanism to

organize and mobilize people into homogeneous conflict groups willing

to fight each other for resources that are at best indirectly linked to

their ethnic identity’ (Wolff 2006, 64–65). Ethnicity and religion are not

synonyms but they frequently overlap. Thus it seems safe to conclude

that religion – as any other factor – can be part of the picture but cannot,

alone, be a cause of conflict.

Fox (2003) has demonstrated that self-determination and nationalism

are the primary causes of ethnic conflicts, while religious factors

can influence the dynamics of the conflict and increase its intensity.

Furthermore, religion causes violence only when it is combined with

these other factors (Fox 2004b). Fox (2001) specifically examines

the role of religion in conflicts in the Middle East and their resulting

characteristics, based on the Minorities at Risk dataset and religious

factors, and he finds that religion plays a disproportionately important

role in ethno-religious conflicts in the region, more so than in non-

Middle Eastern states with Muslim majorities. States in the Middle

East are also disproportionately more autocratic than in other regions.

However, despite the unique importance of religion, Fox argues that

the prevalence of religious conflict is not explained by either the Islamic

or autocratic character of the states, and in reality the ethno-religious

conflicts in the Middle East are not significantly different from similar

ethnic struggles around the world. This, he concludes, contradicts

Huntington’s (1993) notion of Islam’s ‘bloody borders’, as the conflicts

in the Middle East are not more violent than other ethnic conflicts. He

warns, however, that actions based on Huntington’s notion could lead to

a self-fulfilling prophecy. In a further study also based on the Minorities

at Risk dataset, Fox (2004) does argue that religious conflict is more

contagious than non-religious conflict; however, only violent conflicts

cross borders while non-violent ones do not.

The nature of grievances and demands in a conflict is central to the

analyses of Svensson (2007) and Fox (2003). Fox argues that ‘when

religious issues are important, they will change the dynamics of

the conflict’, (2003, 125). This can be attributed both to the role of

religious institutions within the state and to the way in which religion

influences international intervention in ethnic conflict. Internally,

religious institutions tend to facilitate a reaction if the grievances have

religious importance; however, if they have no religious importance the

religious institutions often inhibit protest. With regards to international

intervention, Fox maintains that other states are more likely to intervene

if they have religious minorities in common and if the conflict is ethnoreligious.

Using data from international interventions, he shows that

Islamic states are most likely to intervene and that Islamic minorities

are most likely to benefit from that intervention.

Svensson (2007) argues that across religions, where the grievances or

demands are based on explicit religious claims, the negotiated settlement

of conflict is less likely to succeed than if there are no religious

claims. He demonstrates that the chances for negotiated settlement

are not affected if the conflicting parties are from different religious

traditions. Svensson’s argument is based on data from intra-state

armed conflicts between 1989 and 2003, using the Uppsala Conflict

Data Programme. He concludes that efforts should be made to prevent

conflicting parties from developing their demands in religious terms,

given that negotiated settlements are more likely if religious claims are

not involved.

Galtung’s (2014) theory of the peace potential of religions essentially

focuses on the factors that can make religions prone to promoting

violence and then extrapolates from these to identify and develop the

factors that lend to the potential of religions to maintain or build peace,

arguing that the latter can and should be promoted. Although he notes

that different religions have different degrees of potential to promote

peace, he clearly acknowledges that there is no automatic connection

between the belief system of a specific religion and the use of force

by its followers. He also rejects the notion of ‘religious conflicts’, as

conflicts are multi-dimensional and complex and cannot usually be

reduced to only one causal factor (Galtung 2014, 32). To understand the

peace potential of religions, he looks to what extent religions are prone

to promote or reject direct violence and structural violence.

With regard to direct violence, Galtung (2014) argues that the idea of

‘being a Chosen People’ and the value of ‘aggressive missionarism’

built into the core belief system of a religion can lead to direct violence

perpetrated by its followers. ‘Holy War’ and ‘Just War’ become terms

used to justify the use of violence against other people.

He notes that all religions advocate a special relationship with their

god(s) and fellow believers, thus creating in-groups and out-groups.

However, different religions also have different potential to promote

other forms of structural violence, such as economic exploitation and

political repression. Galtung cites the example of slavery, which was

legitimised in religious terms by some Christians.

Based on this theory, Galtung develops a generalised model of major

religions in the world and classifies them according to their inherent

potential to reject both direct and structural violence. Most importantly,

he argues that, in general, Hinduism rejects both forms of violence and

thus has a large potential for peace. However, Hinduism is less than

explicit about rejecting direct (physical) violence, and it also tolerates

and promotes structural (cultural) violence through its caste system.

Islam rejects a societal caste system (structural violence), but is prone

to promote direct violence through its doctrine obliging all its followers

to defend the faith. Other religions, in particular Christianity, are predisposed

to promote both structural and direct violence. Galtung clearly

accepts that this theory is a general one, and that there are many possibilities

to cite counter-examples. However, he uses his theory mainly

to justify the need for more dialogue, both intra-religious and inter-faith,

which can promote the peace potential of religions (Galtung 1997).

In the light of the research evidence presented so far, it is clear why

many – if not all – scholars of religion and politics subscribe to the

expression ‘ambivalence of the sacred’; religion itself is also neither

good nor bad, but its power can be used to accelerate violence (bad) or

promote peace (good) across societies (Appleby 2000; Haynes 2011;

Philpott 2007a). Trying to distinguish between ‘religious’ and ‘secular’

violence is not only useless but also dangerous (Cavanaugh 2009)

since, ‘privileging religious explanations also serves to depoliticise

and securitise in the political realm’ (Jackson and Gunning 2011, 382).

The consensus seems to be that while religion should not be taken

for granted as the main driving force of violence and conflict, it cannot

be excluded from accounts of international relations, impacting both

interstate relations and domestic politics (see among others Fox 2004a;

Thomas 2005).

Islam and Conflict

Since the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, Islam has been centre

stage when it comes to research on the links between religion and

conflict. Popular commentaries facilely point to the ideological sources

of conflict, maintaining that the Qur’an is inherently violent and that all

forms of Islamism are nothing but an antecedent of violence, terrorism

and totalitarianism. Indeed, a dataset of suicide attacks from 1981 to

March 2008 shows not only an escalation of these from 2000 onwards,

but also that ‘most contemporary suicide attacks can be attributed to

jihadist groups’ (Moghadam 2009), while until recently the evidence

(from a study taking into account data up to 2003) was that secular and

religious groups had been responsible for a roughly equal number of suicide

actions (Pape 2003). Several scholars, including Moghadam (2009)

and Khosrokhavar (2005) have shown how key the religious ideology of

martyrdom is to explaining this sudden rise of Islam-motivated suicide

missions. Yet other experts on Islam and terrorism play down – without

ignoring – the ideological component. In their view, the escalation of

violence carried out in the name of Islam must be attributed to a combination

of factors where contextual variables, individual psychologies and

opportunity structures in a society are central (Hafez 2003; Jackson and

Gunning 2011; Mandaville 2007; Wiktorowicz 2005a). Looking at entire

processes rather than examining individual factors, ideas or actors

appears to be more productive in capturing the shifting role of religion,

and of Islam more specifically, in the current challenges of conflict and

terrorism that the international community faces.

Certainly, Islamic State and other jihadist groups legitimise themselves

through a repertoire of ‘ideas that have broad resonance among

Muslim-majority populations’ (Hamid 2014). But the fact that radical

jihadi groups resort to Islamic sources to justify their violent acts cannot,

on its own, prove that Islam is inherently violent. Rather, as Wiktorowicz

(2005b, 94) argues, it demonstrates their tactical ability to frame

violence in Islamic terms, which is possible thanks to a gradual ‘erosion

of critical constraints used to limit warfare and violence in classical

Islam’. Many, therefore, have urged moderate Muslims to pre-empt this

manipulation of Islamic knowledge. Yet, Moghadam (2009, 78) warns,

we have to recognise that the factors involved in this type of terrorism

are multiple and diverse and that ‘the battle against suicide attacks will

not be won by exposing the inconsistencies of Salafi jihad alone’.

Following Gellner (see section 2.1.) we could argue that the central

problem is not the religious truth itself, but the exclusivist mindset of

those appropriating and disseminating it. Similarly, for Berman (2007),

the origin of conflict lies not in religion, but rather in extremist thinking,

be it radical Islam/Islamism (which he calls ‘Muslim totalitarianism’),

Christian religious fundamentalism, fascism, secular dictatorships, or

extreme authoritarianism. During the twentieth century, violent conflict

on the international scene was caused by such extremist thinking, rather

than by religion per se. It is also important to remember that adherence

to strict religious practices or conservative views is no guarantee

that fundamentalism has been embraced (Brekke 2012). And while

it has often been the case that violent actions have stemmed from

fundamentalist beliefs, no automatic mechanism has been identified

whereby fundamentalism entails violence (Almond et al.2002).

Terrorism studies experts often seem to look at religion through

a narrow lens that focuses only on ideology. Rapoport (2002) was

central in popularising the term ‘religious’ (or faith-based) terrorism

with his theory of the ‘waves’ of terrorism, while others categorised

it as ‘new’ (Laqueur 1999; Neumann 2009). Juergensmeyer (2003)

warns against the cosmologies of violence emanating from religion,

and Hoffman (2006) too stresses the powerful role of religious

narratives and the position of religious leaders in legitimising acts of

violence. However these scholars are also careful not to demonise

religion per se, and they all acknowledge too that other factors need

to be taken into consideration. For instance, according to Rapoport

(2002), the latest – current – wave of religious terrorism includes

features of previous waves of terrorism (i.e. anarchy, self-determination,

socialism). Even someone like Juergensmeyer (2003), who believes

that religion has provided the motivation, world view and organisation

for either conducting or supporting acts of terrorism, acknowledges

that other contextual variables also need to be addressed in each case

being examined.

Based on a quantitative comparison of Islam-related terrorist attacks

between 1968 and 2005, Piazza (2009, 63) accepts that ‘religiouslymotivated

terrorist groups are indeed more prone than are secular groups to committing attacks that result in greater casualties’. He shows that in that period ‘Islamist groups were responsible for 93.6 per cent of all terrorist attacks by religiously-oriented groups and were responsible for 86.9 per cent of all casualties inflicted by religiously-oriented terrorist groups’ (Piazza 2009, 64). However he demystifies the assumption that Islamist terrorism is more ‘lethal’ than other types of terrorism, by pointing out the constellations of ideologies that fall under the nebulous term

‘Islamism’ and that besides religious ideologies and practice, one should

also focus on groups’ ‘organisational features’ and ‘goal structures’. On

the basis of this type of analysis, he argues, only Al Qaeda and similarly

structured groups are likely to be seriously dangerous.

Many have also asked whether economic factors have a role to play

when people engage in terrorism and in faith-based political violence.

Research by Krueger (2007) as well as by Piazza (2006) and by Canetti

et al. (2010) has found no evidence that poverty or loss of economic

resources are predictors of engagement in terrorism. However, Canetti

et al. (2010) did find that distress and loss of ‘psychological’ (rather than

economic) resources do have a correlation with religion in the context

of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Piazza, on the other hand, argues that

state repression and party politics are important predictors of terrorism

(2006) and that countries with minority groups experiencing economic

discrimination have a significant likelihood of being exposed to domestic

terrorist attacks (2011).

Another line of interpretation puts aside religious values and beliefs

to focus instead on particular individuals in privileged/elite positions

within particular religious traditions and communities. Once again,

the argument is not that religion itself leads to violence, but that it is

manipulated by opportunistic and power-thirsty (faith or political) leaders

who appropriate religious language for their own ends. Toft (2007, 103)

has named this phenomenon ‘religious outbidding’; that is, ‘elites

attempt to outbid each other to enhance their religious credentials

and thereby gain the support they need to counter an immediate

threat’. Typically religious language is used to cultivate the identity of

those mobilised and to reinforce out-group markers of the ‘other’. This

process, Stewart (2009) notes, does not happen all at once, but takes

place over a long period of time. Apart from using religion for grand

causes, it is often the case that leaders resort to it to promote their own

underlying interests and so again it is not religion per se that contributes

to conflict but rather the way it is used within societies.

Following this line of analysis, Toft shows that compared with either

Christianity or Hinduism, Islam was greatly over-represented in civil

wars in the twentieth century. She argues that political leaders in the

Islamic world used religion to lend themselves greater legitimacy,

and thus increase their capacity to mobilise the population and

strengthen their power base (Toft 2007). De Juan (2015) arrives at

a similar conclusion in his study of religious elites in intrastate conflict

escalation. Besides providing ‘quotidian norm setting’, religious

leaders ‘communicate specific narratives and shape the religious

self‑conception of the believers’ and are also crucial in the ‘constitution

of radical religious conflict interpretations’ (De Juan 2015, 764). His work

examines ‘the motives of religious elites to call for violence’ rather than

‘the structural prerequisites of their success’. Using case studies from

Thailand, Iraq and the Philippines, he shows that ‘competing religious

elites try to mobilize their followers against their rivals to establish

their predominance within their religious community’ (De Juan 2015,

765). He also notes that in this competition ‘for material and dogmatic

supremacy’, these religious elites become inclined to promote violence,

establish alliances with political elites and thus become triggers of

intra‑religious and intrastate conflicts (De Juan 2015, 762).

Religion and State Failure

There appears to be a strong correlation between the emergence of

religious conflict and situations of state failure or collapse. Fox (2007),

for instance, tracks state failures between 1960 and 2004, identifying

the shifts in the role of religion and state failure. Using data from the

State Failure dataset, he identifies an increase in state failure related

to religion as a proportion of all state failures during this period, and

finds that it became the most common kind of state failure in 2002,

after which he identifies religion as an element in the majority of all

conflicts that relate directly to state failure.

Since 11 September 2001, state failure and state collapse have been

associated with terrorism and labelled as the ‘Orthodox Failed States

Narrative’, which developed based on the experience of the rise of the

Taliban in the collapsed state of Afghanistan (Verhoeven 2009). Several

studies argue that there was an increase in Islamic extremism in the

state failures experienced in Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia in the 2000s.

However, they also differ in how much the various authors emphasise

the role of religion as a cause of increased extremism and offer different

explanations for the phenomenon.

Mwangi (2012), for example, identifies the combination of state collapse

and Islamism in Somalia as accounting for the legitimacy gained by

Harakat Al-Shabaab Al Mujaheddin (Al-Shabaab), a non-state armed

extremist group that provided local governance in Somalia, confirming

the fears that arise from the Orthodox Failed State Narrative. He

portrays Islamism not as a theological construct but as a political

ideology that helps provide answers to the contemporary social and

political challenges facing the Muslim world. Mwangi argues that radical

Islam is most powerful as a mobilising tool when Muslim populations

feel threatened by secular or Christian states. Following Hoehne (2009),

he links the rise and radicalisation of Al-Shabaab with the joint American-

Ethiopian anti-terror strategy, as well as the difficulties the Somali

people faced under conditions of state collapse, which left the country

with no central authority.

Religion as a Driver of Peace

Academic and policy-oriented literature on religion and international

affairs is rich in publications arguing that religion is a useful – if not

necessary – instrument for achieving peace. More specifically, religious

beliefs/values, religious leaders and faith-based organisations are

thought to have huge potential in promoting peace in any society and/

or in the international arena. Scholars in the US (Johnston and Sampson

1994; Johnston 2003; Appleby 2001; Gopin 2000; Smock 2002; Shah et

al. 2012; Coward and Smith 2004; Little 2007) seem to be leading this

school of thought. In fact, ‘faith-based’ diplomacy was invented in the

US (see for example the journal The Brandywine Review of Faith & International

Affairs). The US Institute of Peace has developed substantial

resources for interfaith projects and publications, and the US government

recently created an office for ‘religious engagement’ in the State

Department (Johnston and Cox 2003; Mandaville and Silvestri 2015).

However, some important works in this vein are emerging in Europe

too (e.g. Thomas 2005; Galtung and MacQueen 2008). In addition to the

academic literature, numerous faith groups and NGOs are also mobilising

and producing policy reports to promote and enhance the contribution

by religious actors to development and reconciliation.

Religious Beliefs and Values

In The Ambivalence of the Sacred, Appleby (2000) emphasises that

ethics and ethical convictions, as expressed through religious beliefs,

are main drivers for peace. Regardless of which religion may be prevalent,

the ethical power of religion can help to unite divided societies.

For Thomas (2005) too, religion has a role to play, especially as it can

facilitate a dialogue about ‘virtues’ for shaping a better society. However,

while acknowledging this and the useful characteristics of faith-based

networks and NGOs, he warns against a reductionist approach, in which

an instrumentalist perspective of religion and a logic of problem-solving

prevail while the need to address other issues and involve other actors

is downplayed or discounted. prevail while the need to address other issues and involve other actors is downplayed or discounted.

References to the Christian contribution to non-violence and

peacebuilding are abundant. The key concepts are reconciliation,

which is based on God’s own reconciliation with a sinful humanity,

the powerful model of Jesus’ self-sacrifice to redeem humanity, and

his invitation to ‘turn the other cheek’, and finally his attention to the

poor and the marginalised that encourages Christians to care about

the dignity of the human person. In Christianity, there is a close

relationship between social justice and reconciliation; one cannot

happen without the other. This helps to explain the important work

of Christian denominations in mediation and in promoting transitional

justice (see Philpott 2007b). Christian values are also at the heart of the

Western conception of human rights, even though a parallel, at times

competitive, secular account exists. In the aftermath of World War II,

the work of Christian denominations and the ecumenical movement

were important pillars for the peaceful reconstruction of Europe and in

the establishment of the European Communities (see Thomas 2005;

Byrnes and Katzenstein 2006; Leustean 2014), even though the project

of European integration later took a highly secular and liberal character,

focused mainly on economic and political reasoning.

The majority of case studies in textbooks on religion and politics refer to

mediation work or interfaith activities promoted by Christian denominations,

such as those done in South Africa with Archbishop Desmond

Tutu, in Mozambique with Sant’Egidio, in the US with Martin Luther

King, and also the courageous work in Nigeria, the Middle East and the

Balkans of various priests (see Thomas 2005; Little 2007; Smock 2002;

Lederach 1996, 1997). Buttry (1994) elaborates on the Christian heritage

of non-violence and peacebuilding. He argues that Christian teaching and

values provide the foundations for ‘Christian peacemaking’, i.e. Christianity

provides a whole set of non-violent responses to conflicts worldwide,

both within and between societies (for a similar argument see also

Friesen 1986). The work of Sampson and Lederach (2000) is often regarded

as landmark research in demonstrating the pioneer role played by

Mennonite communities in the history of their non-violent contributions

to peacemaking. In addition, Quakers and Jehovah’s Witnesses, two

groups that are part of the Christian family, have also made explicit their

pacifist stance and rejection of violence (MacCulloch 2010).

Muslim scholar Abu-Nimer (2003) argued that Islam is based on fundamental

human values encoded in the Qur’an, related religious writings

and the Islamic tradition. Based on those values, Muslim societies have

developed a considerable set of non-violent tools for conflict resolution

and peacebuilding experiences. Traditional Arab‑Muslim mechanisms

for dispute resolution include third-party mediation and arbitration

in any form of social conflict. Such mechanisms also included traditional

reconciliation methods, based on the value of forgiveness and

public repentance.

Abu-Nimer (2003) also looks at how Islam developed a theory of de

facto just war principles, both referring to jus ad bellum and jus in bello:

‘War is permissible in self-defense, and under well-defined limits. When

undertaken, it must be pushed with vigour (but not relentlessly), but

only to restore peace and freedom of worship of Allah. In any case,

strict limits must not be transgressed: women, children, old and infirm

men should not be molested, nor trees and crops cut down, nor peace

withheld when the enemy comes to terms’. At the same time, Islam

has a tradition of non-violent resistance, also cited by Abu-Nimer (2003),

which is exemplified by peaceful protests against British colonial rule in

Egypt in 1919, the 1948 Iraqi uprising, the Iran Revolution in 1978–79,

and the Sudanese insurrection of 1985.

Galtung and MacQueen (2008) analyse in detail the contribution

to peacemaking by Asian religions such as Buddhism or Taoism,

with reference to Galtung’s general theory of mentioned above.

By presenting the ideas of 18 eminent Buddhist leaders, Chappell

(1999) enlarged the understanding of Buddhist peacemaking traditions.

Starting from and underlining the central role of achieving inner peace,

he emphasises that Buddhism has a strong track record of providing

peaceful answers to social and political violence, in particular through

its worldwide grassroots work, and points to the responsibility

that Buddhists have for promoting peace. However, others critique

Buddhism for being too much of an individualistic tradition that does

not really stress the importance of being at peace with the others, and

note that it has missed opportunities to achieve peaceful solutions,

in Sri Lanka and Tibet for example (Neumaier 2004).

Religious Leaders and Religious Organizations

A rich strand of research – including a number of works commissioned

by DFID – has examined the role of faith-based organisations

and religious leaders in promoting the peaceful resolution of conflicts

through mediation. Faith-based mediation is seen as an important

contributor to conflict resolution and peace. However, no work sees this

as a complete substitute to traditional diplomatic avenues. The pioneering

work of Johnston and Sampson (1994) brought together scholars

emphasising the comparative advantage of religious actors. Basing their

findings on case studies from East Germany, Philippines, South Africa

and Zimbabwe, they argued that individuals that based their work on

either religious or spiritual thinking were in a better place to reach out to

regional and local actors than were politicians that did not. Similarly, Cox

et al. (1994) argued that religion can be well suited for resolving particularly

prolonged, stalemated or intractable conflicts. The key characteristics

associated with (typically local) religious leaders that enable them to

help in situations of conflict include authority, trust, professionalism and

also cultural and practical/experiential closeness to the people involved

(see among others: Lederach 1996; 1997; Smock 2002).

On a pragmatic level, especially when conflict resolution and peacekeeping

are proceeding in collaboration with development programmes,

religious organisations and leaders have also proven particularly effective

in delivering aid and effective development projects. This is because

faith communities, in addition to being trusted, are inexpensive and they

work rapidly, relying on wide networks of volunteers that are fervently

devoted to the cause and ready to put their lives on the line. This has

proven to be more effective than the work of the salaried staff of large

and bureaucratic international organisations and secular NGOs (Barnett

and Stein 2012).

Bercovitch and Kadayifci-Orellana (2009) focus on the conditions conducive

to the success of faith-based mediation, finding that the legitimacy

and leverage of religious actors can be powerful factors in promoting

successful mediation processes. Aroua (2010) makes a case for mediators

who have a deep understanding of religious beliefs and ideals,

which enables them to promote interreligious dialogue by translating

codes from one value system to another (‘mediators as translators’).

Funk and Woolner (2001) emphasise the role of inter-faith dialogue in

promoting conflict resolution.

Even when peace processes do not lead to a sustainable peace,

religion is nonetheless thought to positively contribute to peace as it

can help build trust between and among social groups and individuals.

Scholars have also noted that many conflicts do not have a religious

component, but that even when that is the case religious leaders can

often play a beneficial role in promoting peace (Aroua 2010).

Religious movements and leaders may also promote the setting of

national and international norms on peace, and generally contribute to

worldwide peace by changing the international discourse on religion and

peace. The historic contribution by Martin Luther King to the spread of

non-violent resistance and international and national anti-discrimination

laws is a prominent example for peace-generating dynamics, discussed

extensively in the scholarly literature.

Case studies have analysed the transformative power of religion and

contributed to scholarly thinking on what religions have in common,

rather than on what divides them. Appleby (2001) gives examples from

different faith traditions: the Catholic NGO Sant’Egidio that promotes

ethical values in conflict situations in Africa and uses mediation as

a tool to promote peace; Buddhist actors promoting human rights in

Cambodia; and Muslim communities that successfully promote peace

in parts of the Middle East. More recently, his work has focused on

‘Catholic approaches to peacebuilding’, looking at the work of many

transnational Catholic NGOs such as Caritas, and exploring how Catholic

social teaching and the ‘preferential option for the poor’ have been

gradually expanded to go beyond social and economic development,

towards ‘reconciliation’ (Schreiter et al. 2010). Michel (2008) specifically

focuses on the role that transnational Islamic movements play in

fostering non-violent relations in the Muslim world. The commitment

to positive societal change, personal transformation, and interreligious

dialogue is fundamental for these movements. ‘Study’ and ‘service’

are key elements underpinning the thinking of their adherents

(Michel 2008).

Bibliography

Abu-Nimer, M. (2001) ‘Conflict Resolution, Culture, and Religion: Toward a Training

Model of Interreligious Peacebuilding’. Journal of Peace Research 38(6): 685–704.

Abu-Nimer, M. (2003) Nonviolence and Peace Building in Islam: Theory and Practice.

Gainsville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Abu-Nimer, M. (2004) ‘Religion, Dialogue, and Non-Violent Actions in Palestinian-Israeli

Conflict’. International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 17(3): 491–511.

Abu-Nimer, M. (2011) ‘Religious Leaders in the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict: From Violent

Incitement to Nonviolence Resistance’. Peace and Change 36(4): 556–580.

Akbaba, Y. and Taydas, Z. (2011) ‘Does Religious Discrimination Promote Dissent?

A Quantitative Analysis’. Ethnopolitics: Formerly Global Review of Ethnopolitics

10(3–4): 271–295.

Alger, C. F. (2002) ‘Religion as a Peace Tool’. Global Review of Ethnopolitics 1(4):

94–109.

Almond, G., Appleby, S. and Sivan, E. (2002) Strong Religion: The Rise of

Fundamentalisms Around the World. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Aly, A. and Striegher, J.L. (2012) ‘Examining the Role of Religion in Radicalization to

Violent Islamist Extremism’. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 35(12): 849–862.

Amnesty International (2012) Mali. Les Civils Paient un Lourd Tribut au Conflit. London:

Amnesty International.

Appleby, S. R. (2000) The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence and

Reconciliation. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Appleby, S. R. (2001) ‘Religion as an Agent of Conflict Transformation and

Peacebuilding’. In Crocker, C. A. et al. (eds.). Turbulent Peace: The Challenges of

Managing International Conflict. 2nd Ed. Washington, DC: United States Institute

of Peace Press, 821–840.

Arboff, M. J. (1999) ‘Political Violence and Extremism’. Israel Studies 4(2): 237–246.

Armstrong, H. (2013) ‘A Tale of Two Islamisms’. New York Times, 25 January. [Online]

Available from: http://nyti.ms/11WJwuZ

Aroua, A. (2010) ‘Danish ‘Faces of Mohammed’ Cartoons Crisis: Mediating

Between Two Worlds’. In Aroua, A. et al. (eds.). Transforming Conflicts with

Religious Dimensions: Methodologies and Practical Experiences. Zurich: The

Centre on Conflict, Development and Peacebuilding/CCDP, 34–35.

76 The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding // British Academy

Asad, T. (1993) Genealogies of Religion. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins

University Press.

Asad, T. (2003) Formations of the Secular. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Associated Press (2013) ‘Mali – Al-Qaida’s Sahara Playbook’. Letter by Abdel-Malek

Droukdel, written to his fighters in Mali. [Online] Available from http://hosted.

ap.org/specials/interactives/_international/_pdfs/al-qaida-manifesto.pdf

Barnett, M. and Stein, J. (eds.) (2012) Sacred Aid: Faith and Humanitarianism.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bar-Siman-Tov, Y. (2010) ‘Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’.

Jerusalem Institute for Israeli Studies 406: 228–263.

Bercovitch, J. and Kadayifci-Orellana, A. S. (2009) ‘Religion and Mediation: The Role of

Faith-Based Actors in International Conflict Resolution’. International Negotiation

14, 175–204.

Berdal, M. (2003) ‘How ‘New’ Are ‘New Wars’? Global Economic Change and the

Study of Civil War’. Global Governance 9(4): 477–502.

Berkovitch, N. and Moghadam, V. N. (1999) ‘Middle East Politics and Women’s

Collective Action: Challenging the Status Quo’. Social Politics 6(3): 273–291.

Berling, J. (2004) ‘Confucianism and Peacebuilding’. In Coward, H. and Smith,

G. (eds.). Religion and Peacebuilding. New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Berman, P. (2007) ‘Terror and Liberalism’. International Security 31(4): 97–131.

Best, S. G. and Rakodi, C. (2011) Violent Conflict and its Aftermath in Jos and Kano,

Nigeria: What is the Role of Religion? Religions and Development Research

Programme Working Paper No. 69, International Development Department,

University of Birmingham. [Online] Available from: http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/PDF/

Outputs/Inequality/workingpaper70.pdf

Bhatt, C. (2001) Hindu Nationalism. Oxford and New York: Berg.

Biggar, N. (2013) In Defence of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bitter, J-N. (2003) Les Dieux Embusqués. Une Approche Pragmatique de la

Dimension Religieuse des Conflits. Genève/ Paris: Librairie DROZ.

Bitter, J-N. (2009) ‘Tajikistan: Relationships between State and Religious

Organizations’. In Transforming Conflicts with Religious Dimensions:

Methodologies and Practical Experiences, Conference Report, 27–28 April. Zurich:

The Centre on Conflict, Development and Peacebuilding/ CCDP, 32–33.

Bøås, M. and Torheim, L. E. (2013a) ‘Mali Unmasked: Resistance, Collusion,

Collaboration’. NOREF: Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre Report. [Online]

Available from www.peacebuilding.no/var/ezflow_site/storage/original/ application/

36b5ec0050cfeaa4fa14121de29ac9c1.pdf

Bøås, M. and Torheim, L. E. (2013b) ‘The Trouble in Mali – Corruption, Collusion,

Resistance’. Third World Quarterly 34(7): 1279–92.

Boudreau, G. (2014) ‘Radicalization of the Settlers’ Youth: Hebron as a Hub for Jewish

Extremism’. Global Media Journal – Canadian Edition 7(1): 69–85.

Boulding, E. (1986) ‘Two Cultures of Religion as Obstacles to Peace’. Zygon: Journal of

Religion and Science 21(4): 501–518.

Brekke, T. (2012) Fundamentalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

British Academy // The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding 77

Bryden, M. (2003) ‘No Quick Fixes: Coming to Terms with Terrorism, Islam,

and Statelessness in Somalia’. Journal of Conflict Studies 23(2): 24–56.

W. (1988) ‘Conflict Resolution as a Function of Human Needs’. In Coate, R. A.

and Rosati, J. A. (eds.). The Power of Human Needs in World Society. London:

Lyne Rienner Publishers.

Buttry, D. L. (1994) Christian Peacemaking: From Heritage to Hope. Valley Forge,

PA: Judson Press.

Byman, D. and Sachs, N. (2012) The Rise of Settler Terrorism: The West Bank’s

Other Violent Extremists. Foreign Affairs 91(5): 73. [Online] Available from:

www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/137825/daniel-byman-and-natan-sachs/the-rise-ofsettler-

terrorism

Byrnes and Katzenstein (eds.) (2006) Religion in an Expanding Europe. Cambridge

and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Carton, E. (2011) Unsettling the Settlement: The Ideology of Israel’s Hilltop Youth.

Senior Thesis. Department of Religion: Haverford College.

Cavanaugh, W. T. (2009) The Myth of Religious Violence: Secular Ideology and the

Roots of Modern Conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chappell, D. W. (1999) Buddhist Peacework: Creating Cultures of Peace. Somerville,

MA: Wisdom Publications.

Callimachi, R. (2013) ‘In Timbuktu, al-Qaida Left Behind a Manifesto’. Associated Press

News, 14 February. [Online] Available from: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/timbuktual-

qaida-left-behind-strategic-plans

Canetti, D., Hobfoll, S., Pedahzur, A. and Zaidise, E. (2010) ‘Much ado about religion:

Religiosity, resource loss, and support for political violence’. Journal of Peace

Research 47(5) 575–587.

Cline, A. n.d. ‘Religious Wars in the Balkans’. About Agnosticism/ Atheism. [Online]

Available from: http://atheism.about.com/library/weekly/aa033199.htm, 3 Jan 2015.

Coleman, D. Y. (2014) ‘Mali: 2014 Country Review’. Country Watch Review. [Online]

Available from: www.countrywatch.com/Intelligence/CountryReviews?

CountryId=109

Collier, P., L. Elliott, H. Hegre, A. Hoeffler, M. Reynal-Querol, N. Sambanis. (2003)

Breaking the ConflictTrap: Civil War and Development Policy. Washington, DC;

New York: World Bank; Oxford University Press.

Coolsaet, R. (ed.) (2011) Jihadi Terrorism and the Radicalisation Challenge.

Farnham: Ashgate.

Coward, H. and Smith, G. S. (2004) Religion and Peacebuilding. Albany, NY:

SUNY Press.

Cox, H. with Sharma, A., Abe, M., Sachedina, A., Oberoi, H. and Idel, M. (1994) ‘World

Religions and Conflict Resolution’. In Johnston, D. and Sampson, S. (eds.). Religion,

the Missing Dimension of State-Craft. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cramer, C. and Goodhand, J. (2002) ‘Try Again, Fail Again, Fail Better? War, the

State, and the ‘Post-Conflict’ Challenge in Afghanistan’, Development and

Change 33(5): 885–909.

De Juan, A. (2015) ‘The Role of Intra-Religious Conflicts in Intrastate Wars’,

Terrorism and Political Violence 27(4): 762–780.

78 The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding // British Academy

Devlin-Foltz, Z. and Ozkececi-Taner, B. (2010) ‘State Collapse and Islamist Extremism:

Re-Evaluating the Link’. Contemporary Security Policy 31(1): 88–113.

Draft Peace Agreement for Mali (2014) Projet D’Accord la Paix et la Reconciliation au

Mali, 27 November. [Online] Available from: http://malijet.com/docs/Projet_accord_

Alger_NordMali.pdf

Duffy, E. (2004) Faith of our Fathers. London: Continuum.

Fearon, J., and Laitin, D. (1996) ‘Explaining interethnic cooperation’. The American

Political Science Review 90(4): 715–735.

Fearon, J. and Laitin, D. (2003) ‘Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War’. The American

Political Science Review 97(1): 75–90.

Fleischmann, L. (forthcoming) The Transformation of Israel Peace Activism Since the

Second Intifada. PhD Thesis. City University London.

Fox, J. (2000a) ‘The Ethnic-Religious Nexus: The Impact of Religion on Ethnic Conflict’.

Civil Wars 3 (3): 1–22.

Fox, J. (2000b) ‘Book Review: Marc Gopin, Between Eden and Armageddon’.

Millennium Journal of International Studies 29(3): 904–905.

Fox, J. (2001) ‘Are Middle East Conflicts More Religious?’. Middle East Quarterly

8(4): 31–40.

Fox, J. (2003) ‘Counting the Causes and Dynamics of Ethnoreligious Violence’.

Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 4(3): 199–144.

Fox, J. (2004a) ‘Is Ethnoreligious Conflict a Contagious Disease?’. Studies in Conflict

and Terrorism 27(2): 89–106.

Fox, J. (2004b) Religion, Civilization and Civil War: 1945 Through the New Millennium.

Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Fox, J. (2007) ‘The Increasing Role of Religion in State Failure 1960–2004’.

Terrorism and Political Violence 19: 395–414.

Fox, J. and Sandler, S. (2004) Bringing Religion into International Relations. New York,

NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Friedman, R. (1986) ‘Inside the Jewish Terrorist Underground’. Journal of Palestine

Studies 15(2): 190–201.

Friesen, D. K. (1986) Christian Peacemaking and International Conflict: A Realist Pacifist

Perspective, Scottdale, PA: Herald Press.

Frisch, H. (2005) ‘Has the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Become Islamic? Fatah, Islam,

and the Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades’. Terrorism and Political Violence, 17(3):

391–406.

Frisch, H. and Sandler, S. (2004) ‘Religion, State, and the International System in the

Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’. International Political Science Review, 25(1): 77–96.

Funk, N. C. and Woolner, C. J. (2001) ‘Religion and Peace and Conflict Studies’. In

Matyok, T., Senehi, J. and Byrne, S. (eds.). Critical Issues in Peace and Conflict

Studies. Toronto: Lexington Books.

Galtung, J. (1964) ‘A Structural Theory of Aggression’. Journal of Peace Research 1(2):

95–119.

Galtung, J. (1969) ‘Violence, Peace and Peace Research’. Journal of Peace Research

6(3): 167–191.

British Academy // The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding 79

Galtung, J. (1975) ‘Three Approaches to Peace: Peacekeeping, Peacemaking and

Peacebuilding’. In Galtung, J. (ed.) Peace, War and Defence – Essays in Peace

Research. Vol. 2. Copenhagen: Christian Ejlers.

Galtung, J. (1997/98) ‘Religions, Hard and Soft’. Cross Currents, 47(4): 437–450.

Galtung, J. (2009) ‘Theories of Conflict. Definitions, Dimensions, Negations,

Formations’. [Online] Available from: www.transcend.org/files/Galtung_Book_

Theories_Of_Conflict_single.pdf

Galtung, J. (2012) ‘Religions Have Potential for Peace’. Lecture at the World Council

of Churches’ Ecumenical Centre, 22 May. Geneva: World Council of Churches.

Galtung, J. (2014) ‘Peace, Conflict and Violence’. In Hintjens, H. and Zarkov, D.

(eds.). Conflict, Peace, Security and Development: Theories and Methodologies.

London: Routledge.

Galtung, J. and MacQueen, G. (2008) Globalizing God. Religion, Spirituality and Peace.

Basle: TRANSCEND University Press.

Garfinkel, R. (2004) What Works? Evaluating Interfaith Dialogue Programs. Special

Report 123. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Geertz, C. (1993 [1973]) The Interpretation of Cultures. London: Basic Books.

Gellner, E. (1992) Postmodernism, Reason and Religion. London: Routledge.

Glock, C. Y. and Stark, R. (1965) Religion and Society in Tension. San Francisco,

CA: Rand McNally.

Gnanadason, A., Kanyoro, M. and McSpadden, L.A. (eds.) (1996) Women, Violence

and Non Violent Change. Geneva: World Council of Churches Publications.

Gopin, M. (2000) Between Eden and Armageddon: The Future of World Religions,

Violence, and Peacemaking. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gopin, M. (2001) ‘Forgiveness as an Element of Conflict Resolution in Religious

Cultures: Walking the Tightrope of Reconciliation and Justice’. In Abu-Nimer M.

(ed.) Reconciliation, Coexistence, and Justice in Interethnic Conflicts: Theory and

Practice. Lanham, MD and Oxford: Lexington Books.

Gunning, J. (2009) Hamas in Politics, London: Hurst.

Gurr, T.R. (1993) Minorities at Risk: A Global View of Ethnopolitical Conflicts.

Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Hadley, M. L. (2001) Spiritual Roots of Restorative Justice, New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Hafez, M. (2003) Why Muslims Rebel: Repression & Resistance in the Islamic World.

Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Hamid, S (2014) ‘The Roots of the Islamic State’s Appeal’. The Atlantic, 31 October.

[Online] Available from: www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/10/theroots-

of-the-islamic-states-appeal/382175

Hasso, F. S. (1998) ‘The ‘Women’s Front’ Nationalism, Feminism, and Modernity in

Palestine’. Gender and Society 12(4): 441–465.

Hatina, M. (1999) ‘Hamas and the Oslo Accords: Religious Dogma in a Changing

Political Reality’. Mediterranean Politics 4(3): 37–55.

Hatina, M. (2005) ‘Theology and Power in the Middle East: Palestinian Martyrdom

in a Comparative Perspective’. Journal of Political Ideologies 10(3): 241–267.

80 The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding // British Academy

Haynes, J. (2011) Religion, Politics and International Relations: Selected Essays.

London: Routledge.

Hecht, R. D. (1993) ‘The Political Cultures of Israel’s Radical Right: Commentary on

Ehud Sprinzak’s The Ascendance of Israel’s Radical Right’. Terrorism and Political

Violence 5 (1): 132–159.

Helmick, R. G. and Petersen, R. L. (2001) Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Religion,

Public Policy, and Conflict Transformation. Radnor, PA: Templeton Foundation Press.

Hermann, T. (2009) The Israeli Peace Movement: A Shattered Dream. New York, NY:

Cambridge University Press.

Hérvieu-Léger, D. (2000) Religion as a Chain of Memory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hill, C. (2013) The National Interest in Question. Foreign Policy in Multicultural

Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoehne, M. V. (2009) ‘Mimesis and Mimicry in Dynamics of State and Identity

Formation in Northern Somalia’. Africa 79(2): 252–281.

Hoffman, B. (2006) Inside Terrorism. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Hossein-Zadeh, I. (2005) ‘The Muslim World and the West: The Roots of Conflict’.

Arab Studies Quarterly 27(3): 1–20.

Huntington, S. P. (1993) ‘The Clash of Civilizations?’. Foreign Affairs 72(3): 22–49.

Huntington, S. P. (1997) The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order.

London: Simon and Schuster.

Jackson, R. and Gunning, J. (2011) ‘What’s So “Religious” About “Religious

Terrorism?”’. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 4(3): 369–388.

Jacoby, T. A. (1999) ‘Feminism, Nationalism and Difference: Reflections on the

Palestinian Women’s Movement’. Women’s Studies International Forum 22(5):

511–523.

Jeffrey, P. (2013) ‘Hidden in Timbuktu: An Islamic Legacy Protected from Jihadists’.

Christian Century 130(19): 30–33.

Johnston, D. (ed.) (2003) Faith-Based Diplomacy Trumping Realpolitik, Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Johnston, D. (2005) ‘Faith-Based Organizations: The Religious Dimension of

Peacebuilding’. In Van Tongeren, P. et al. (eds.). People Building Peace II:

Successful Stories of Civil Society. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Johnston, D. and Cox, B (2003) ‘Faith-Based Diplomacy and Preventive Engagement’.

In D. Johnston (ed.) Faith-Based Diplomacy Trumping Realpolitik, Oxford: Oxford

University Press: 11–29.

Johnston, D. and Sampson, C. (1994) Religion, the Missing Dimension of State-Craft.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jok, J.M. (2007) Sudan. Race, Religion, and Violence. Oxford: Oneworld.

Jones, C. (1999) ‘Ideo-Theology and the Jewish State: From Conflict to Conciliation?’.

British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 26(1): 9–26.

British Academy // The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding 81

Juergensmeyer, M. (2003) Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious

Violence. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kakar, S. (1996) The Colors of Violence. Chicago and London: University of

Chicago Press.

Kaldor, M. (2012) New and Old Wars: Organised Violence in a Global Era. Cambridge:

Polity Press.

Kalin, I. (2005) ‘Islam and Peace: A Survey of the Sources of Peace in the Islamic

Tradition Source’. Islamic Studies 44(3): 327–362.

Kaufman, E., Salem, W. and Verhoeven, J. (eds.) (2006) Bridging the Divide:

Peacebuilding in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Boulder, CO and London: Lynne

Rienner Publishers.

Kedourie, E. (1960) Nationalism. London: Hutchinson.

Khosrokhavar, F. (2005) Suicide Bombers: Allah’s New Martyrs. London: Pluto Press.

Kim, S. (2013) ‘Mali’s Religious Scholars Cunningly Save Ancient Islamic Manuscripts

from Salafist Fighters in Timbuktu’. The Independent, 6 February. [Online]

Available from: www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/malis-religiousscholars-

cunningly-save-ancient-islamic-manuscripts-from-salafist-fighters-intimbuktu-

8483952.html

Kivimäki, T., Kramer, M. and Pasch, P. (2012) The Dynamics of Conflict in the Multi-

Ethnic State of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo: Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung. [Online]

Available from: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/sarajevo/09418.pdf

Konaté, D. (1999) ‘Les fondements endogènes d’une culture de paix au Mali: Les

mécanismes traditionnels de prévention et de résolution des conflits’. UNESCO

Report. [Online] Available from: www.unesco.org/cpp/publications/mecanismes/

edkonate.htm, 4 Jan 2015.

Krueger, A. (2007) What Makes a Terrorist: Economics and the Roots of Terrorism.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Küng, H. and Kuschel, K-J. (1993) A Global Ethic: The Declaration of the Parliament of

the World’s Religions. New York, NY: The Continuum International Publishing Group

Inc.

Kushner, H. W. (1996) ‘Suicide Bombers: Business as Usual’. Studies in Conflict

and Terrorism 19(4): 329–337.

Laitin, D. (2007) Nations, States and Violence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Landau, Y. (2003) Healing the Holy Land: Religious Peacebuilding in Israel Palestine.

Washington, DC: Peace Works Series of the United States Institute of Peace.

Laqueur, W. (1999) The New Terrorism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lecocq, B., Mann, G., Whitehouse, B., Badi, D., Pelckmans L., Belalimat N, Hall, B.,

and Lacher W. (2013) ‘One Hippopotamus and Eight Blind Analysts: A Multivocal

Analysis of the 2012 Political Crisis in the Divided Republic of Mali’. Review of

African Political Economy 40(137): 343–57.

Lederach, J. P. (1996) Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures.

Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Lederach, J. P. (1997) Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies.

Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

82 The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding // British Academy

Le Meur, P-Y. and Hochet, P. (2010) ‘Property Relations by Other Means: Conflict

over Dryland Resources in Benin and Mali’. European Journal of Development

Research 22(5): 643–59.

Lemish, D. and Barzel, I. (2000) ‘Four Mothers: The Womb in the Public Sphere’.

European Journal of Communication, 15(2): 147–169.

Leustean, L. (2014) The Ecumenical Movement and the Making of the European

Community. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, B. (1990) ‘The Roots of Muslim Rage’. The Atlantic, September, www.

theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1990/09/the-roots-of-muslim-rage/304643

Little, D. (ed.) (2007) Peacemakers in Action: Profiles of Religion in Conflict Resolution.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Litvak, M. (1998) ‘The Islamization of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict: The Case of

Hamas’. Middle Eastern Studies 34(1): 148–163.

Luckmann, T. (1967) The invisible religion: the problem of religion in modern society.

London: Macmillan.

Luft, G. (2002) ‘The Palestinian H-Bomb: Terror’s Winning Strategy’. Foreign Affairs

81(4): 2–7.

Lustick, I. S. (1987) ‘Israel’s Dangerous Fundamentalists’. Foreign Policy 68: 118–139.

MacCulloch, D. (2004) Reformation: Europe’s House Divided. London: Penguin.

MacCulloch, D. (2010) A History of Christianity. London: Penguin.

Mandaville, P. (2007) Global Political Islam. London and New York, NY: Routledge.

Mandaville, P. and Silvestri, S. (2015) ‘Integrating Religious Engagement into

Diplomacy’. Issues in Governance Studies 67. [Online] Available from: www.

brookings.edu/ ~/media/research/files/papers/2015/01/29-religious-engagementdiplomacy-

mandaville-silvestri/issuesingovstudiesmandavillesilvestriefinal.pdf

Martin, D. (2005) On Secularization: Towards a Revised General Theory.

Aldershot: Ashgate.

Mayall, J. (1990) Nationalism and International Society. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Mayall, J. and Srinivasan, K. (2009) Towards The New Horizon, World Order

in the 21st Century. New Delhi, Standard Publishers.

McGuire, M. (2008) Lived Religion. New York: Oxford University Press.

Merdjanova, I. and Brodeur, P. (2010) Religion as a Conversation Starter: Interreligious

Dialogue for Peacebuilding in the Balkans. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Michel, T. S. J. (2008) ‘Peaceful Movements in the Muslim World’. In Banchoff, T. (ed.).

Religious Pluralism, Globalization, and World Politics. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Milton-Edwards, B. (2006) ‘Political Islam and the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict’.

Israel Affairs 12(1): 65–85.

Moghadam, A. (2009) ‘Motives for Martyrdom’. International Security 33(3): 46–78.

Mwangi, I. G. (2012) ‘State Collapse, Al-Shabaab, Islamism, and Legitimacy in Somalia’.

Politics, Religion and Ideology 13(4): 513–527.

British Academy // The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding 83

Neumaier, E. (2004) ‘Missed Opportunities: Buddhism and the Ethnic Strife in Sri

Lanka and Tibet’. In Coward, H. and Smith, G. (eds.). Religion and Peacebuilding.

New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Neumann, P. (2009) Old and New Terrorism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Newman, D. (2005) ‘From Hitnachalut to Hitnatkut: The Impact of Gush Emunim and

the Settlement Movement on Israeli Politics and Society’. Israel Studies 10(3):

192–224.

Newman, D. and Hermann, T. (1992) ‘A Comparative Study of Gush Emunim and

Peace Now’. Middle Eastern Studies 28(3): 509–530.

Nir, O. (2011) ‘Price Tags: West Bank Settlers’ Terrorizing of Palestinians to Deter Israeli

Government Law Enforcement’. Case Western Reserve Journal of International

Law 44: 277–289.

Pape, R. (2005) Dying to Win. The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism. New York:

Random House.

Patterson, E. (2013) Bosnia: Ethno-Religious Nationalisms in Conflict. Religion and

Conflict Case Studies Series, Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs,

Georgetown University. [Online] Available from: http://repository.berkleycenter.

georgetown.edu/130801BCBosniaEthnoReligiousNationalismsConflict.pdf

Peleg, S. (1997) ‘They Shoot Prime Ministers Too, Don’t They? Religious Violence

in Israel: Premises, Dynamics, and Prospects’. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism

20(3): 227–247.

Philpott, D. (2001) Revolutions in Sovereignty: How Ideas Shaped Modern International

Relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Philpott, D. (2007a) ‘Explaining the Political Ambivalence of Religion’. American Political

Science Review 101(3): 505–525.

Philpott, D. (2007b) ‘What Religion Brings to the Politics of Transitional Justice’.

Journal of International Affairs 61(1): 93–110.

Piazza, J. (2006) ‘Rooted in Poverty? Terrorism, Poor Economic Development, and

Social Cleavages’. Terrorism and Political Violence, 18(1): 159–177.

Piazza, J. (2009) ‘Is Islamist Terrorism More Dangerous? An Empirical Study of

Group Ideology, Organization, and Goal Structure’. Terrorism and Political Violence,

21(1): 62–88.

Piazza, J. (2011) ‘Poverty, Minority Economic Discrimination, and Domestic Terrorism’.

Journal of Peace Research 48(3): 339–353.

Polner, M. and Goodman, N. (1994) The Challenge of Shalom: The Jewish Tradition of

Peace and Justice. Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers.

Post, J. M. (2005) ‘When Hatred Is Bred in the Bone: Psycho-Cultural Foundations of

Contemporary Terrorism’. Political Psychology 26(4): 615–636.

Primo, N. (2013) ‘No Music in Timbuktu: A Brief Analysis of the Conflict in Mali and

Al Qaeda’s Rebirth’. Pepperdine Policy Review 6, 1–17.

Ramsbotham, O., Woodhouse, T. and Miall, H. (2005) Contemporary Conflict

Resolution. 2nd edn. Cambridge and Malden: Polity.

Rapoport, D. (2002) ‘The Four Waves of Rebel Terror and September 11’. Anthropoetics

8:1. [Online] Available from: www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap0801/terror.htm

84 The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding // British Academy

Robinson, B. A. (2007) ‘Religious Aspects of the Yugoslavia – Kosovo Conflict’.

Religious Tolerance, Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance. [Online] Available

from: www.religioustolerance.org/war_koso.htm

Roy, O. (2004) Globalised Islam: The Search for a New Ummah. London: Hurst.

Rubin, A. J. (1999) ‘Religious Identity at the Heart of Balkan War’. Los Angeles

Times, 18 April. [Online] Available from: http://articles.latimes.com/1999/apr/18/

news/mn-28714

Sachedina, A. (2000) The Islamic Roots of Democratic Pluralism. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Said, A. A., Funk, N. C. and Kadayifci, A. S. (2001) Peace and Conflict Resolution in

Islam: Precept and Practice. Lanham, MD, New York, NY and Oxford: University

Press of America.

Said, A. A, Funk, N. C. and Kadayifci, A. S. (2002) ‘Islamic Approaches to Conflict

Resolution and Peace’. The Emirates Occasional Papers, No. 48. Abu Dhabi:

The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research.

Said, E. (2001) ‘The Clash of Ignorance’. The Nation 273(12): 11–14.

Sampson, C. and Lederach, J. P. (2000) From the Ground Up: Mennonite Contributions

to International Peacebuilding. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sandler, S. (1996) ‘Religious Zionism and the State: Political Accommodation and

Religious Radicalism in Israel’. Terrorism and Political Violence 8(2): 133–154.

Sasson-Levy, O., Levy, Y. and Lomsky-Feder , E. (2011) ‘Women Breaking the Silence:

Military Service, Gender, and Anti-War Protest’. Gender and Society 25(6): 740–763.

Schmid, A. (2013) ‘Radicalisation, De-Radicalisation, Counter-Radicalisation:

A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review’, ICCT Research Paper, The Hague.

[Online] Available from: www.icct.nl

Schreiter, R., Appleby, S. R., and Powers G. F. (eds.) (2010). Peacebuilding: Catholic

Theology, Ethics, and Praxis. Maryknoll, NY:Orbis Books

Scott, P. and Cavanaugh, W. T. (eds.) (2007) The Blackwell Companion to Political

Theology. Oxford: Blackwell.

Shah, T., Stepan, A. and M. Toft (eds.) (2012) Rethinking Religion and World Affairs.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shakman Hurd, E. (2007) The Politics of Secularism in International Relations.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sharoni, S. (1995) Gender and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Politics of Women’s

Resistance. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Shinn, D. (2003) ‘Terrorism in East Africa and the Horn: An Overview’. Journal of

Conflict Studies 23(2).

Silvestri, S. (2010) ‘Public Policies towards Muslims & the Institutionalisation of

“moderate” Islam in Europe: some critical reflections’. In A. Triandafyllidou (ed.)

Muslims in 21st century Europe. London: Routledge, 45–58.

Singh, R. (2012) ‘The Discourse and Practice of ‘Heroic Resistance’ in the Israeli-

Palestinian Conflict: The Case of Hamas’. Politics, Religion and Ideology 13(4):

529–545.

British Academy // The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding 85

Skidmore, M. (2007) ‘Introduction’. In Skidmore, M. and Lawrence, P. (eds.) Women

and the Contested State. Religion, Violence, and Agency in South and Southeast

Asia. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press.

Skidmore, M. and Lawrence, P. (eds.) (2007) Women and the Contested State.

Religion, Violence, and Agency in South and Southeast Asia. Notre Dame, Indiana:

University of Notre Dame Press.

Skoko, B. (2010) ‘What Croats, Bosniaks and Serbs Think of Each Other and What do

They Think About BH’. Bozo Skoko, 19 November. [Online] Available from: www.

bozoskoko.com/en/news/commentaries/what-croats-bosniaks-and-serbs-thinkeach-

other-and-what-do-they-think-about-bh

Smock, D. R. (1995) Perspectives on Pacifism: Christian, Jewish and Muslim Views

on Non-Violence. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Smock, D. R. (ed.) (2002) Interfaith Dialogue and Peace Building. Washington, DC:

United States Institute of Peace Press.

Smock, D. R. (2009) ‘Nigeria: Religion as Identity, Religion as Bridge’. In Transforming

Conflicts with Religious Dimensions: Methodologies and Practical Experiences.

Conference Report, 27–28 April. Zurich: The Centre on Conflict, Development and

Peacebuilding/ CCDP), 26–27.

Soares, B. F. (2006) ‘Islam in Mali in the Neoliberal Era’. African Affairs 105(418): 77–95.

Soares, B. F. (2013) ‘Islam in Mali since the 2012 coup’. Cultural Anthropology , 10 June,

http://production.culanth.org/fieldsights/321-islam-in-mali-since-the-2012-coup

Spahic-Šiljak, Z. (2010) Women, Religion and Politics. Sarajevo: IMIC, CIPS, TPO.

Spahic-Šiljak, Z. (2012) Contesting Female, Feminist and Muslim Identities –Post-

Socialist Contexts of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. Sarajevo: CIPS,

University of Sarajevo Press.

Spahic-Šiljak, Z. (2014) Shining Humanity – Life Stories of Women Peacebuilders in

Bosnia and Herzegovina. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Sprinzak, E. (1987) ‘From Messianic Pioneering to Vigilante Terrorism: The Case of the

Gush Emunim Underground’. Journal of Strategic Studies 10(4): 194–216.

Sprinzak, E. (1991a) The Ascendance of Israel’s Radical Right. New York, NY: Oxford

University Press.

Sprinzak, E. (1991b) ‘Violence and Catastrophe in the Theology of Rabbi Kahane: The

Ideologization of the Mimetic Desire’. Terrorism and Political Violence 3(3): 48–70.

Sprinzak, E. (1998) ‘Extremism and Violence in Israel: The Crisis of Messianic Politics’.

Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 555: 114–126.

Sprinzak, E. (1999) Brother Against Brother: Violence and Extremism in Israel Politics

from Altalena to the Rabin Association. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Steele, D. (2011) A Manual to Facilitate Conversations on Religious Peacebuilding and

Reconciliation. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Stefanov, J. (2012) Peaceful Life in a Land of War: Religion & the Balkan Conflicts.

World Student Christian Federation – Europe, 13 August [Online] Available from:

http://wscf-europe.org/mozaik-issues/peaceful-life-in-a-land-of-war-religion-and-thebalkan-

conflicts

86 The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding // British Academy

Steinberg, G. M. (2000) ‘Conflict Prevention and Mediation in the Jewish Tradition’.

Jewish Political Studies Review, Special Issue: Jewish Approaches to Conflict

Resolution, 12(3–4): 3–21.

Stewart, F. (ed.) (2008) Horizontal Inequalities and Conflict: Understanding Group

Violence in Multi-Ethnic Societies. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stewart, F. (2009) Religion Versus Ethnicity as a Source of Mobilisation:

Are There Differences? CRISE Working Paper No. 70, Oxford: Centre for Research

on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity, and London: Department of

International Development). [Online] Available from: http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/PDF/

Outputs/Inequality/workingpaper70.pdf

Stückelberger, C. (2012) Lecture at the World Council of Churches’ Ecumenical Centre

22 May. Geneva: World Council of Churches.

Svensson, I. (2007) ‘Fighting with Faith: Religion and Conflict Resolution in Civil Wars’.

The Journal of Conflict Resolution 51(6): 930–949.

Talbot, I. (2007) ‘Religion and violence: the historical context for conflict in Pakistan’.

In Hinnells, J.R and R. King (eds.). Religion and Violence in South Asia. London and

New York: Routledge, 154–172.

Taub, G. (2007) ‘God’s Politics in Israel’s Supreme Court’. Journal of Modern Jewish

Studies 6(3): 289–299.

Taylor, C. (2007) A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Tessler, M. (1994) A History of the Arab–Israeli Conflict. Bloomington, IN: Indiana

University Press.

Thomas, S. (2005) The Global Resurgence of Religion and the Transformation of

International Relations. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Toft, M. (2007) ‘Getting Religion? The Puzzling Case of Islam and Civil War’.

International Security 31:4, 97–131.

United Nations (2013) Security Council Resolution 2100, S/RES/2100, 25 April.

[Online] Available from: www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp? symbol=S/

RES/2100(2013)

UNFPA (2014) Religion and Development Post 2015. New York: UNFPA. [Online]

Available from: www.unfpa.org/publications/religion-and-development-post-2015

Verhoeven , H. (2009) ‘The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy of Failed States: Somalia,

State Collapse and the Global War on Terror’. Journal of Eastern African Studies

3(3): 405 425.

Waseem, M. (2010) ‘Dilemmas of Pride and Pain: Sectarian Conflict and Conflict

Transformation in Pakistan’. Religions and Development Research Programme

Working Paper No. 48, Department of Management Sciences, Lahore University.

[Online] Available from: http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/PDF/Outputs/ReligionDev_RPC/

working_paper_48.pdf

Weaver, D. J. (2001) ‘Violence in Christian Theology’. Cross Currents 51(2): 150–176.

Weingardt, M. A. (2007) Religion macht Frieden. Das Friedenspotential von Religionen

in politischen Gewaltkonflikten. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

British Academy // The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding 87

Weingardt, M. A. (2008a) ‘Das Friedenspotential von Religionen in Politischen

Konflikten. Beispiele Erfolgreicher Religionsbasierter Konfliktintervention’.

In Brocker, M. und Hildebrandt, M. (eds.). Friedensstiftende Religionen?

Religion und die Deeskalation Politischer Konflikte. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für

Sozialwissenschaften.

Weingardt, M. A. (2008b) ‘Religion als Friedensressource. Potenziale und Hindernisse’.

Wissenschaft und Frieden, 2008–3: Religion als Konfliktfaktor. [Online] Available

from www.wissenschaft-und-frieden.de/seite.php?artikelID=1484 .

Wiktorowicz (2005a) ‘A Genealogy of Radical Islam’. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism

28: 75–97.

Wiktorowicz (2005b) Radical Islam Rising: Muslim Extremism in the West. Lanhan:

Rowman & Littlefield.

Wilkes, G. R., Zotova, A., Kuburic, Z., Andrejc, G., Brkic, M., Jusic, M., Momcinovic,

Z. P. and Marko, D. (2013) ‘Factors in Reconciliation: Religion, Local Conditions,

People and Trust. Results from a Survey Conducted in 13 Cities Across Bosnia and

Herzegovina in May 2013’. Diskursi – Special Issue. Sarajevo: Centre for Empirical

Research on Religion.

Wise, C. (2013) ‘Plundering Mali’. Arena Magazine 123: 34–37.

Wolff, S. (2006) Ethnic Conflict: A Global Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wolff, S. (2011) ‘The regional dimensions of state failure’. Review of International

Studies 37: 951–972.