July 18-August 1, 2017

Marlene Laruelle (GWU) and Sophie Hohmann (INALCO, Paris)

This PIRE fieldwork was devoted to the study of social urban sustainability in two cities of Sakha Republic (Yakutia): the capital city Yakutsk and the “diamond capital” Mirnyi. Our research focused on demographic, social and cultural changes in Russia’s Far North cities. We collected local statistical data and organized interviews with local diasporas and migrant communities. We also met with officials from the republican-level Ministry of External Affairs, Center for Strategic Studies, House of Friendship, and several scholars from different research centers at the North-Eastern Federal University and curators from local museums.

The “Yakutization” of Yakutsk

Yakutsk is a unique case in the Russian Arctic because it is a city which has been able to avoid massive depopulation. If the republic lost some of its population during the depressed 1990s, the city itself has continued to show a rare dynamism, growing from 196,600 inhabitants in 1989 to 303,800 in 2016. This dynamism is fed by the massive arrival of the titular rural population to the capital city. Such a movement of people is a unique phenomenon: no other city in the republic of Sakha receives a similar influx of rural residents.

Yakutsk is attractive because it is seen as part of a process of climbing the social ladder by the rural population, especially young generations. Several overlapping phenomena explain this attraction:

- the departure of Russians for European Russia (about 200,000 have left since the collapse of the Soviet Union, or 35% of the Russian population of the city);

- the promotion of the titular nationality in the republican administration;

- being the main higher education center in the republic; the local universities and institutes, especially North-Eastern Federal University, the Medical Academy and the State Agricultural Academy, attract mostly young members of the titular nationality.

As Figure 1 shows the number of Russians steadily collapsed after 1989, while the number of Yakuts grew without disruption since the 1950s.

Figure 1. Ethnic distribution of Russian and Yakut population in Yakutia by censuses

Our research also focused on the niches occupied by a third category of the population, that of labor migrants, coming from the South Caucasus and Central Asia. The two main ethnic groups are Armenians and Kyrgyz, representing two different patterns of migration. Armenians benefit from a “pull” factor, that of a small diaspora already present in the city in the 1970s-1980s, while numerous Kyrgyz arrived only in the 2000s. It is difficult to obtain statistics from the Federal Migration Service at the municipal level, and many migrants remain undocumented. However, we know that the city of Yakutsk hosted 2,200 Armenians and 2,900 Kyrgyz with Russian citizenship during the 2010 census.

These diaspora and migrant communities occupy specific economic niches: mostly the construction sector—a booming sector given Yakutsk’s demographic growth—followed by the car repair business, and the shoes repair sector for Armenians. Some other groups such as Uzbeks—mostly from Southern Kyrgyzstan, therefore Kyrgyz citizens—dominate the fruit and vegetable import market, especially wholesale bazaars. Many migrants come only for the summer months (from 2 to 5 months) to make money and spend the winter in their home country.

Diaspora and migrant cultural life is organized around two main institutions: the ethnic associations represented at the House of Friendship (Dom druzhby), in charge of folkloric activities (celebration of national holidays, traditional dances and songs), and the religious buildings. The Armenian community built a church in 2014, thanks to a group of generous Armenian businessmen, and is waiting for a permanent priest. The mosque has existed longer: it was erected in 1997 by some members of the Ingush diaspora, and was totally rebuilt in 2014, to receive a growing number of Muslims, including some Yakuts and Russians converted to Islam. The mosque is multinational, with Ingush, Tajiks and Uzbeks being the most numerous attendees to religious services.

The Armenian Church and the Mosque

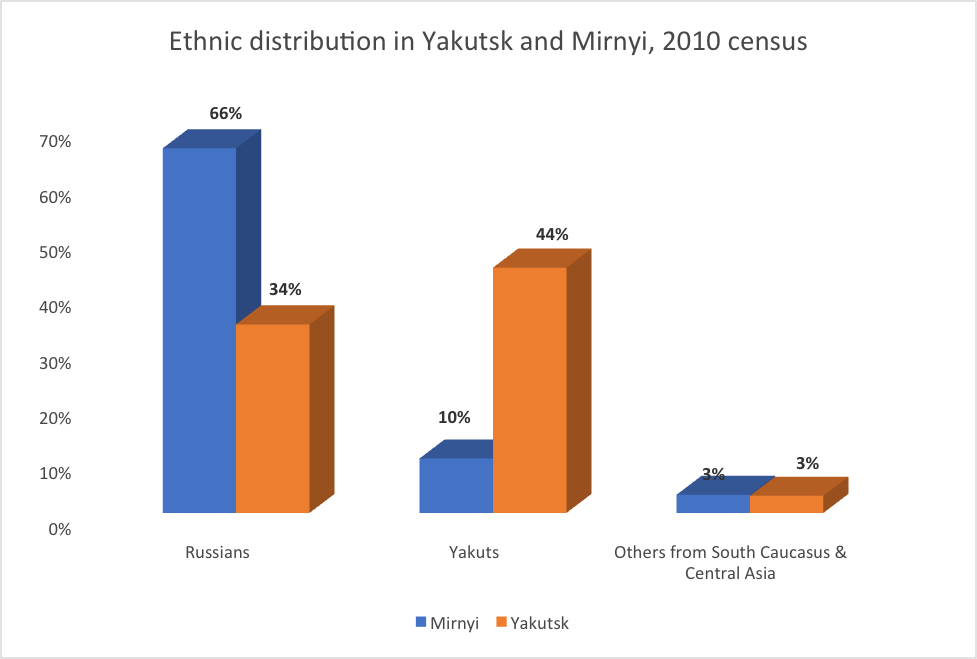

Mirnyi offers a totally different outlook of urban development. The diamond capital is a monotown entirely dominated by Alrosa, Russia’s partially state-owned diamond company. Like all other cities of the republic with the exception of Yakutsk, the city is not facing a Yakutization process: Russians remain largely dominant, comprising 24,000 people of 37,000 total inhabitants. There are only 3,600 Yakuts (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Ethnic distribution in Yakutsk and Mirnyi, 2010 census

A large part of the population works for Alrosa and its subsidiaries: over the whole Mirnyi district, Alrosa employs about 40,000 people from a total of 96,000. As the city’s main mine stopped working in 2001, diamond extraction increasingly takes place in other small towns of the district, such as Aykhal and Udachnyi, by long-distance commuting workers based in Mirnyi. There too, migrants are present, with Kyrgyz being the first diasporic ethnic group, working in the construction sector and trading clothes and everyday items, while Uzbeks control the fruit and vegetable kiosks. The city hosts a mosque and veiled women are visible in the streets of the city. A similar trend is noticeable in other industrial cities: in Nenyungri for instance, the second city of the republic with 60,00 inhabitants, between 10,000 and 15,000 residents are Muslim, though there are only 1,800 Yakuts.

The city and the mine of Mirnyi seen from the sky

Housing for long-distance commuting workers in Aykhal

Sakha-Yakutia therefore displays a dual urban development pattern: the capital city of Yakutsk displays rapid demographic growth and indigenization, thanks to a diversified economy and its status as a republican administrative center, while all the other cities (Mirnyi, Nenyungri, Lensk, Aldan), centered on extraction industries, remain demographically stable and dominated by Russians.