The city center in Luleå, Sweden, is a tree-lined pedestrian- and bicycle-only thoroughfare lined with shops and restaurants. The city buildings are, with few exceptions, only a few stories tall. At the periphery stand a few apartment buildings, each four to five stories tall, and most in the same iconic colorful batten on board construction as the houses in the surrounding neighborhood. On a weekday, the city hums with life: commuters headed to work on city buses, shoppers with their pull-behind wheeled carts, young parents following toddlers on stride bikes, and a gaggle of middle-school-aged girls headed to the beach. Gingerbread rooflines and lush green spaces throughout and surrounding the city lend a quiet storybook charm to the city.

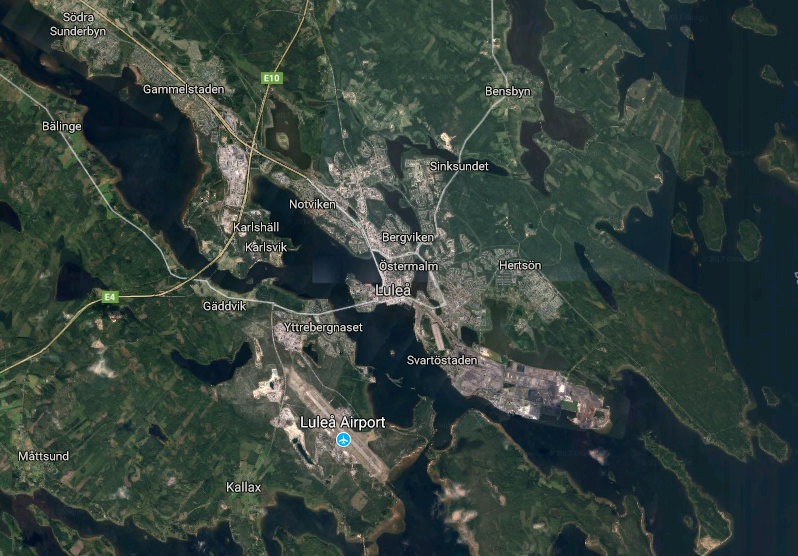

Luleå is a low-density city, and many of the city’s residents live in neighborhoods well beyond the city center. The sprawl of Luleå is partly due to the topography—the coastal city encompasses a number of islands and peninsulas and has developed around the numerous inlets and lakes, but increasing the density of the city center would decrease the breadth of sprawl and concentrate a greater percentage of the population in the city. Would increasing the density of Luleå’s city center, however, decrease the quality of life for the city’s residents? Does an increase in density necessarily decrease green space, community space, or other spaces that contribute to the well-being of a city’s residents? These are important questions to consider, as density is a key quality for sustainability in terms of resource use in urban centers, but excessively high density or poorly managed density can negatively impact the health and social sustainability of a city.

Poorly managed density leads to overcrowding. There may be a minimum threshold of square footage of dwelling space per person required to not be considered overcrowded, but generally overcrowding is linked to management and perception. Population density in a stadium is not perceived as problematic, but a much lower level of density feels intolerable in highway traffic. The perception and tolerance for density or overcrowding is informed in part by cultural factors: levels of acceptable density are perceived differently in Kolkata and Stockholm. Overcrowding can be thought of as the stress experienced because of too high a population density in a given set of circumstances (Kutner 2016). Overcrowding, rather than population density, can lead to increased tension between residents and sometimes result in violence. From a management perspective, overcrowding is the result of inadequate management and provision of resources such as water, electricity, and housing.

In Jakarta, Indonesia, high population density has led to overcrowding because of inadequate infrastructure (IRIN 2010; Hamer 2014). Without sufficient clean water sources, adequate roads and transportation networks, or sewage treatment, the quality of life for residents is extremely low, and the city has been ranked as one of the worst in Asia for ease of doing business. Recent efforts to improve transportation through increased rail transit has thus far been stymied by lack of funding and poor coordination between levels of government (Hamer 2014).

High-density, low-rise development is the ideal for urban layouts, striking a balance between efficiency and quality of life, but small dwelling units are required to adequately increase urban density (Patel 2011). High-density development increases the efficiency with which municipal services can be provided, creates economies of scale, and preserves the surrounding natural environment. High-density urban development is also a prerequisite for effective public transportation networks, an important component for achieving urban sustainability. A 1977 study by Boris S. Pushkarev and Jeffery M. Zupan shows that public transit works best where residential density exceeds 4200 persons per square mile.

High-rise buildings and vertical cities (high-rise buildings with other self-contained municipal functions such as water treatment and power generation) offer one potential solution to increase density in cities and maximize efficiency in transportation, infrastructure, and service provision. But high-rise living is not without its drawbacks. First, not everyone is interested in this type of lifestyle- young, single men are generally the most amenable to the idea. Second, high-rise living can present some health challenges: children’s physical development may be stifled by the constraints of available play facilities; respiratory infections are more prevalent among women and children living in high-rise buildings; and high density developments can have a negative influence on mental health by reducing community interaction and increasing tensions (Wong 1998; Young 1976).

Population growth, migration, and urbanization in Arctic cities mimics global urbanization trends. With two-thirds of the world’s population predicted to live in cities by the year 2050 (UN 2014), it’s important to consider urban density and management to increase sustainability, improve quality of life, and decrease the negative effects of overcrowding.