During the summer of 2017, the PIRE team made a field trip to Salekhard and Vorkuta in Russia. Here we present a report on the trip from GW Grad Student Luis Suter.

This research trip represented an evolution of a 10-year annual field course, started by the GW-based Arctic CALM project. The field courses were originally focused on educating students on the proper field methods for collecting and measuring permafrost characteristics such as ground temperature, soil composition, and

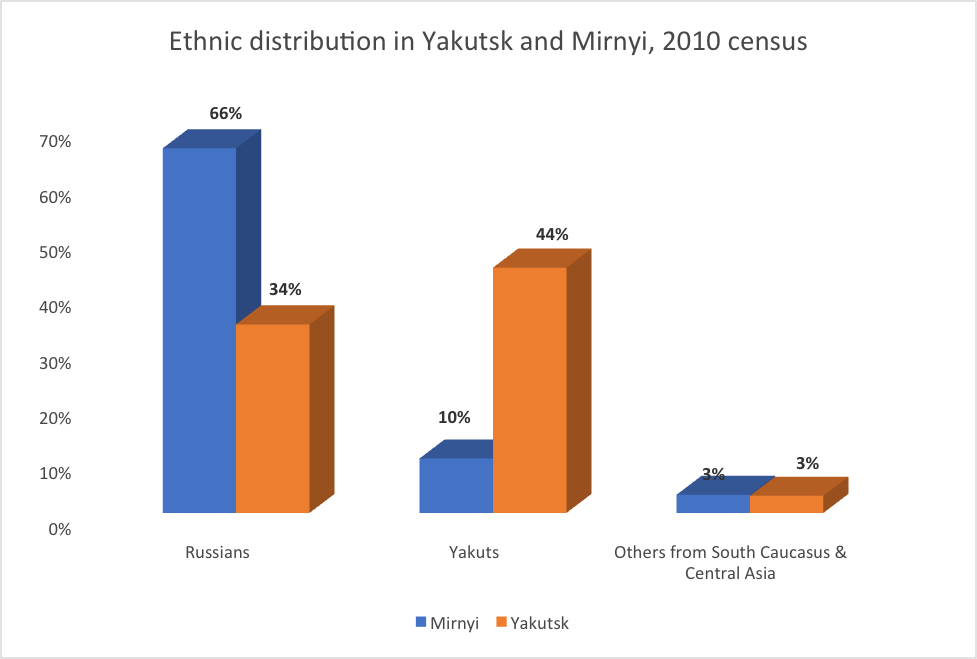

monitoring changes in active layer thickness. With the integration of the Arctic PIRE project, the field course was expanded to include Arctic urban sustainability themes. These included resource-based boom-bust cycles, urban planning and governance, migration-related social issues, and economic diversification.

The field course also focused on promoting exchanges among the international group of students participating.

The course included students from the United States, Russia, Germany, Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland (Figure 1). This group, led by four instructors, visited Salekhard in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Orkrug and Vorkuta in the Komi Republic (Figure 2).

Students spent alternating days conducting fieldwork in the tundra and in these cities, while participating in nightly lectures given by both students and professors. Students learned to consider sustainability in the Arctic as an interdisciplinary issue, related to both physical variables such as climate, permafrost, and geology and anthropogenic factors including economic development, migration, and governance.

In the tundra, the group undertook the collection of permafrost and active-layer data in a variety of Arctic landscapes. The students learned traditional techniques, as well as modern technologies, used to measure environmental parameters important to permafrost health (Figure 3).

Aside from these principles of geocryology and how this data can be used in research, students discussed the visible impacts of anthropogenic influence and climate change on the field sites. The impressions of human activity were near-constant, from the scars of old vehicle tracks covered in cotton-grass (Figure 4) to contemporary roads and rail-lines.

While in the urban settings, students engaged with local government officials, urban planners, research centers, museums, and universities to learn about socioeconomic and governance issues in the Arctic. Meetings and presentations with research organizations, including the Arctic Research Center and Center for Economic Development, produced valuable connections for the Arctic PIRE research network. By visiting Salekhard, a city rich with gas resources, and Vorkuta, a declining coal-mining city, students were able to learn about the effects of boom-bust economic cycles through living realities

(Figure 5). Discussions with local representatives from both cities allowed this international group to debate concepts and strategies for sustainable development in the region, particularly in the face of a rapidly changing climate.

Encouraging the ability to view an issue from multiple angles is critical. The exchange of ideas between this diverse group of students, professionals, and locals promoted the growth of this international perspective through research and education. For many students it was the first time in the Arctic. Through their first-hand exposure to the complex interactions of environment, economics, society, and politics within the region, these students walked away as improved scientists and global citizens.