Public transportation is an important contributing factor to urban sustainability. Effective transportation networks that incorporate public transit help lower a city’s per capita carbon footprint, and make cities more livable by easing commute and transportation needs and increasing accessibility. But the mere presence of public transportation—the number of buses, trains, trolleys, and trams available—does not paint a complete picture. The Sustainable Cities Institute names five principles of sustainability for municipal transportation: accessibility; affordability; connectivity; holistic transportation and land use planning; and planning with the environment in mind.

Holistic transportation, land use planning, and planning with the environment in mind means that transportation systems include many elements including streets, sidewalks or pedestrian networks, transit, bicycle routes, plus private and public fleets. Those elements interface effectively with both the physical geography and commercial and residential development, and account for other environmental factors such as seasonal trends and extreme weather.

Transit-oriented development (TOD) is a development approach that focuses on land use around a transit hub or within a transit corridor. The Sustainable Cities Institute describes TOD as characterized by mixed use land, moderate to high density, pedestrian-oriented, reduced parking, and multiple transportation choices. The definition may be relatively new, but the fundamental idea of development built around transportation is ancient. Cities have always sprung up alongside rivers not only for the water source for personal and commercial consumption, but especially as modes of transportation for people and cargo, facilitating trade. The oldest known human civilization, Mesopotamia, developed in a river valley, along with settlements along the Nile, the Indus, and the Yellow Rivers. In the U.S., historically industrial cities like Allentown, Pennsylvania, and Cincinnati, Ohio, are clustered around rivers.

Though an ancient idea, TOD responds to modern calls for sustainable urban development in response to climate change, increased urbanization and demand for walkable cities, rising energy prices, and increased road congestion with increasing urban density. TOD can address some of the environmental, social, and economic challenges in implementing sustainable transportation networks including fuel sources including fossil fuels and resultant greenhouse gas emissions, and renewable energy; funding challenges; commuting costs; and human health.

In May 2017, Arctic PIRE researchers travelled to Anchorage, AK, where many civic and community leaders expressed that one significant sustainability challenge that the city faces is a poor relationship between the physical layout of the city and the transit network. The city is low density, sprawled over quite a large area, and was not developed around a transit corridor, nor has the transit network been adequately developed to connect the city. This has resulted in reliance on personal automobiles, low ridership on city buses, and poor accessibility for those who rely entirely on public transportation. The bus system was also not particularly accessible to tourists- as visitors, the system seemed labyrinthine and service was too infrequent to be functional for our needs. Forthcoming changes to the system (planned for October 2017) promise a more sustainable transit system with streamlined service, bus stops in closer proximity to people and jobs, and increased frequency of routes particularly during weekday commutes.

Some cities in Sweden’s Arctic demonstrate more sustainable transportation systems. At a national level, Sweden has committed to a fossil-fuel independent public bus fleet by 2030, already resulting in a 43% decrease in public bus emissions between 2007 and 2014 (Xylia and Semida 2017). These gains have been more pronounced in southern counties, while in the northernmost counties of Norrbotten and Västerbotten, buses still rely overwhelmingly on fossil fuels. At a municipal level, both Umeå (in Västerbotten) and Luleå (in Norrbotten) are making strides towards decreasing their bus emissions. Umeå has recently begun transitioning their bus fleet to battery-powered buses, a move that has been a proof-of-concept of the suitability of battery-powered vehicles for cold environments. Luleå’s intent to limit the environmental impact of transportation in spite of continued growth, part of its aspirational sustainable development plan “Vision 2050,” is illustrated in the growing fleet of biogas buses.

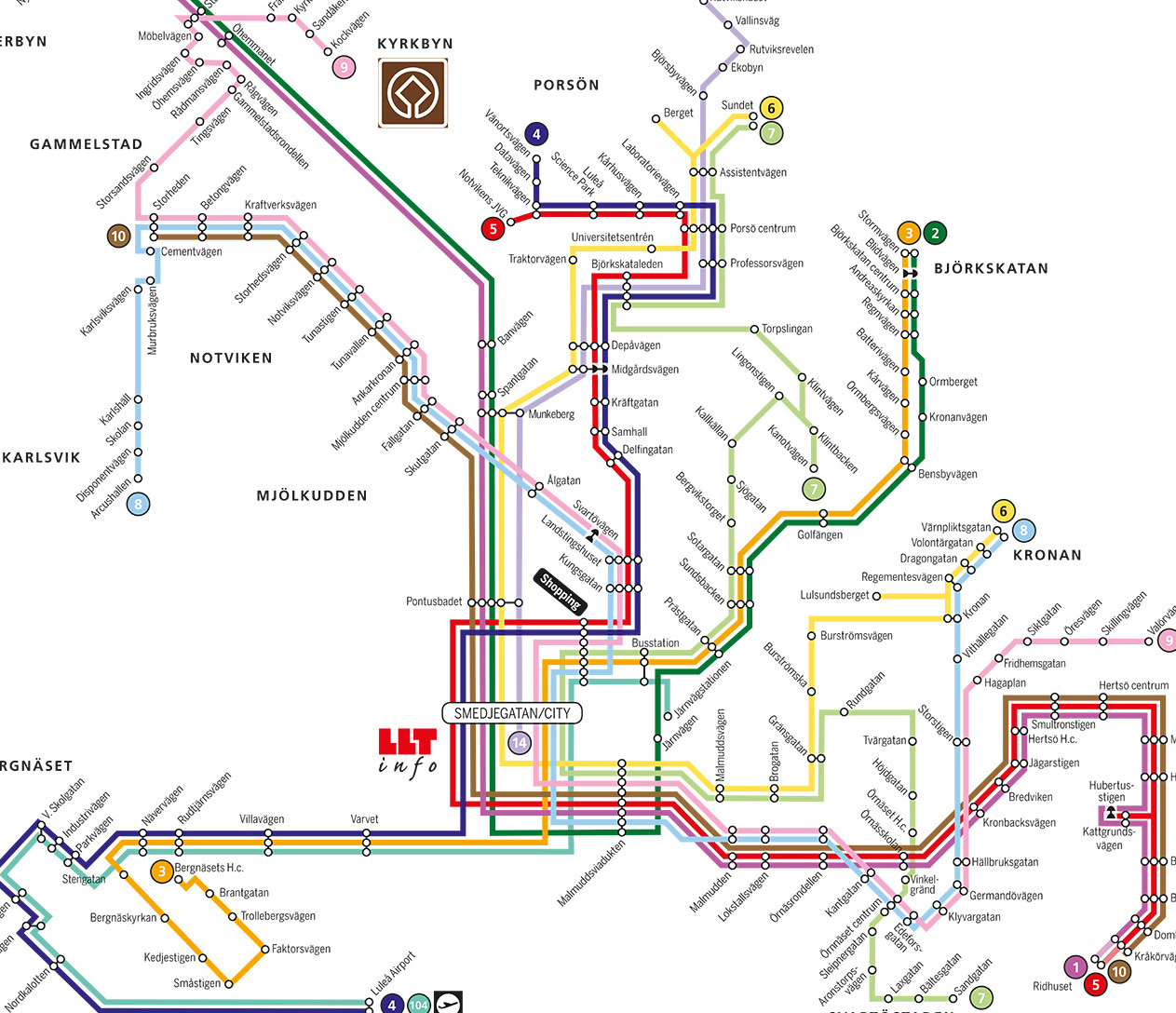

In addition to high efficiency vehicles, alternative fuel, and TOD, Luleå is also building its sustainable transportation network through demand management, traffic calming, and connectivity between multiple forms of transportation. Systems that use real-time data to provide information for planners on ridership and help manage demand while also providing riders accurate information on bus timetables, routes, and arrival times. Restricted access for vehicles in the city center, designated lanes for bikes and buses, and narrowed city streets act as traffic calming measures keeping the city center pleasant and accessible for workers and residents. The transit hub in the city center is a stop on nearly all local bus routes, and is immediately adjacent to the pedestrian and bicycle thoroughfare. Bicycle parking is plentiful near bus stops, city buses are equipped with bike racks, and regional buses allow bicycles as cargo. A central bus station serves both local and regional buses and is located across the street from the train station, thus providing seamless connectivity for those traveling to and from areas outside the city. These connections, along with a city that has protected pedestrian and bicycle networks, means that individuals can travel easily using a combination of walking, biking, buses, and trains.

Urban transportations that increase affordability, accessibility, and connectivity, while incorporating good land use planning and environmental considerations significantly contribute to urban sustainability. As Arctic cities grapple with increasing urbanization, migration, climate change, and economic challenges, sustainable transportation systems can decrease environmental impact while increasing social and economic sustainability.

Resources