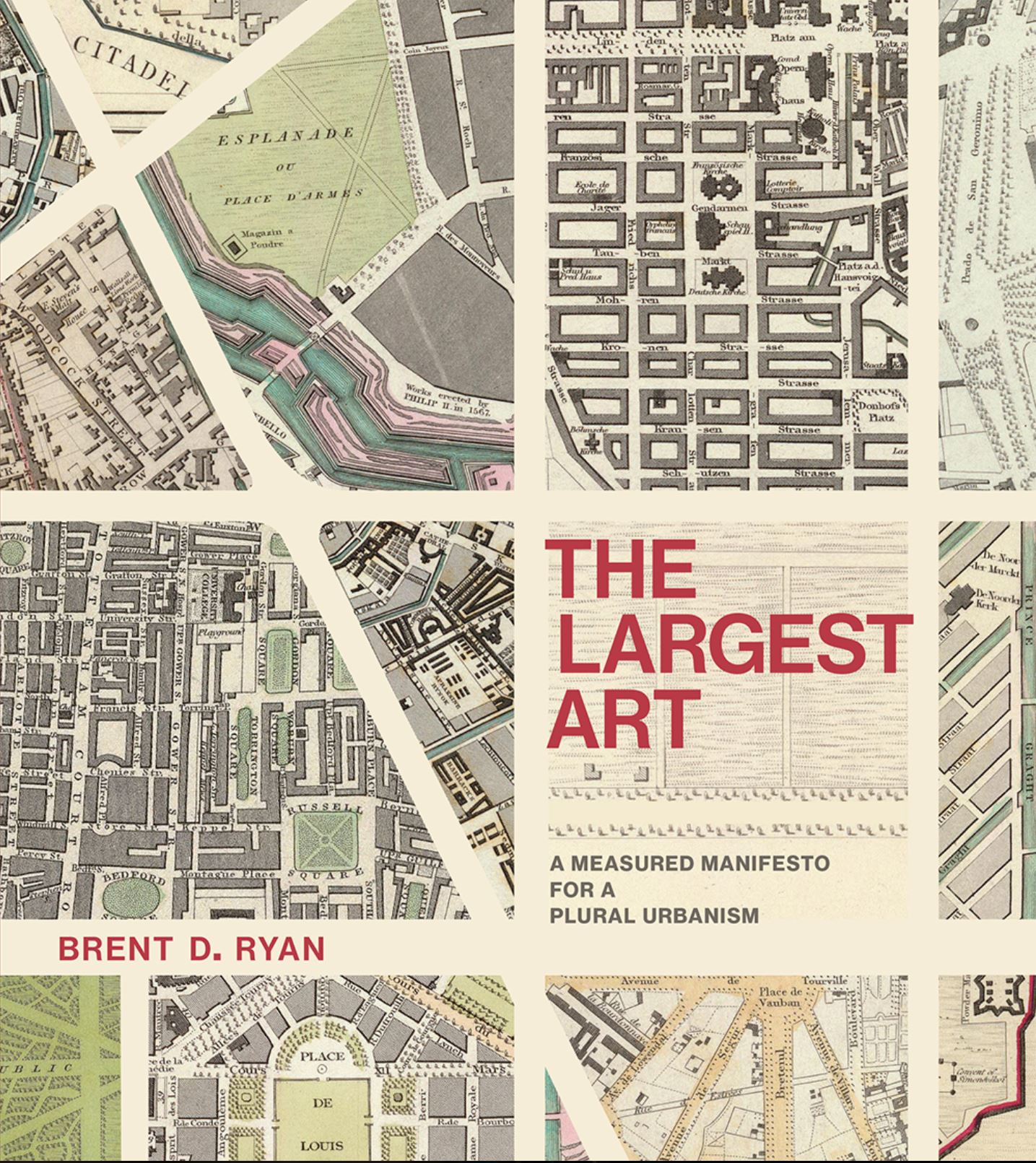

Brent D. Ryan, The Largest Art: A Measured Manifesto for a Plural Urbanism, Cambridge: MIT University Press, 2017.

Book Review

By Robert Orttung

In addition to being a member of the PIRE family, Brent Ryan recently published a spellbinding book that seeks to set a new direction for urban design after it fell into a dead end more than a decade ago. Urban design needed Brent’s intervention because it no longer was able to reconcile theoretical debates with the human needs of cities and citizens, according to architecture critic Michael Sorkin, who published an influential essay making this point in 2006.

The Largest Art: A Measured Manifesto for a Plural Urbanism will reshape the conversation about cities and how they grow. The book is extremely ambitious in its aims and largely successful in its execution. This work of one person opens the doors for all of us to engage – or, really, re-engage with greater vigor – in the life and design of the cities we inhabit.

The purpose of the book is a “declaration of independence” for urban design from other building arts such as architecture, landscape, sculpture and land art. The book provides “a descriptive theory explaining the many qualities that distinguish urban design (urbanism)” and make it an art unto itself with its own characteristics.

The subtitle of the book describes the book as a “measured manifesto” and I wondered what that term meant as I was reading. I speculated that Brent was saying that he was too polite to savage the works of other authors whose ideas he rejected. Rather, on page 309 he finally explained that “measured” means this tome is not a declaration of independence after all but a call for a recognition of urban design’s independence that has always existed.

Well, although the book is a collection of ideas plucked from various sources, it presents a new and original stew, so I would have gone with a straight up manifesto! One gets the impression that architects are a rather autocratic bunch and it is much more pleasant to spend time with the democratic Dr. Ryan.

Brent distinguishes plural urbanism from unitary urbanism and this is the key innovation of the text. The author notes that the term pluralism is “widespread in studies of politics and society” and he “borrowed it for its broad meaning of multiplicity or manyness (p. xi).” In this conception urban design is a “building art” that “accepts those elements of cities that are beyond designers’ direct control – other buildings, other owners, other actors – and that then incorporates them into urban design.” Urban design thus becomes more powerful, wide-ranging, influential, and beneficial than something done by a single designer. It is “more democratic, participatory, open-ended, and infinite (p. 2).” It is not utopian, but practical.

Five key features define the idea of plural urbanism (Chapter 2):

- Scale – plural urbanism ranges from a pocket park on a city street to a metropolitan region

- Time – building a small ensemble can take 40 years whereas elements in cities like Barcelona can span hundreds of years

- Property – each bit of land in a city is owned by someone and urban design must work across these numerous owners

- Agency – cities are inhabited by people who participate in its constuction, and

- Form – any urban design could have 2-3 constitutive elements or dozens and the urban design concept can be diffuse, scattered or fragmented without losing its coherence.

The conclusion lays out three additional concepts that define plural urbanism: change, incompleteness, and flexible fidelity. In other words, cities are always changing and urban designers need to accept this reality. Cities are by their nature incomplete and even many projects developed by architects remain unfinished. Finally, it is not necessary for the designer to impose his or her vision on the city. Rather, the many actors who live in a city will inevitably put their stamp on it, though a good plural designer can nudge the results in aesthetically pleasing and more effective directions.

One problem with plural urbanism is that it is hard to picture. It is easy to conjure up figures of unitary urbanism, which is simply architecture on a larger scale. But how do you show a city that is changing over time and scale thanks to the contributions of many hands? Presumably, 3D graphics and virtual reality will lead the way, but this technology is only beginning to emerge.

In the spirit of the ideas developed here, it is no criticism to say that the book itself is incomplete. The text is meant to start a conversation about the future of cities. As a political scientist, what struck me most was that the text does not really interrogate the idea of pluralism in all its forms. For students of politics, pluralism is an idea associated with Robert Dahl, the political theorist whose works included Who Governs? (1961) about pluralist politics in the city of New Haven and Polyarchy (1971), one of the seminal contributions to democratic theory.

In this sense, plural urbanism draws our attention to some tensions, but then papers over them. A case in point is this passage describing how the inhabitants of an island try to get a grip on a crisis of overdevelopment that is destroying what everyone loves about the place they live by setting up a committee to address the issue:

The committee’s membership spans the range of constituencies concerned with the island’s future. Each municipality is represented, together with representatives of the state’s environmental, housing, and transportation departments, the island’s open space and heritage nonprofits, a few concerned citizens, and an urban design firm hired from outside the state. The risk of design by committee is avoided from the outset: the committee’s recommendations will be strictly advisory, and final recommendations will come from the design firm. Even in this democratic, actively participatory context, the committee recognizes that action is more important than discussion. (p. 226)

Of course, that is not how things work in the real world. My neighborhood in Northern Virginia is currently debating how to build a new school and some of the authorities are pushing an option that is unpopular with most of the neighborhood stakeholders, creating howls of protest. Simply having a discussion and then taking a decision everyone has to accept is the definition of “democratic centralism” which was practiced by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union until its demise in 1991. While the problem of moving from words to construction is real, painful, and time-consuming, plural urbanism needs to take these social processes more into account. In fact, is there much future for a plural urbanism in a society that is becoming increasingly polarized and even less able to agree on anything?

Rhetorical questions aside, The Largest Art presents plenty of ways for urbanism to be plural. Its various chapters provide concrete examples of urban pluralism in locations ranging from Romania, New York City, and Ljubljana, interprets the works of twentieth century urban designers who developed bits and pieces of the ideas incorporated into this manifesto, and even lays out how the ideas developed here can be applied in the future. The most interesting idea for me was David Crane’s concept of a capital web. In shaping the nature of new development, the urban designer could build out a spine of infrastructure which would define the shape of future growth, but allow others to develop the actual buildings and spaces in between that make up the ever-changing fabric of the city.

Although this book does not address the Arctic specifically, it lays out lots of ideas, like the capital web, that could be relevant there. Like any good book, and urban pluralism itself, this one launches a new conversation that will inform how we think about cities and act to improve their design for many years to come.