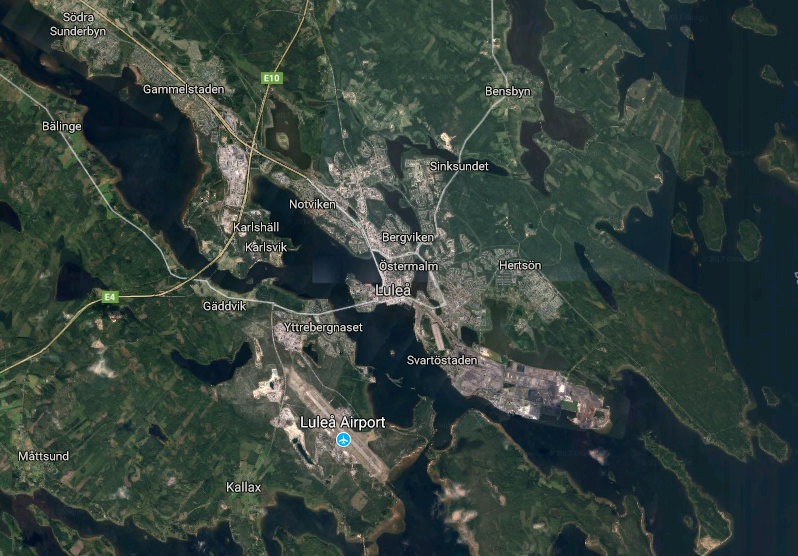

Over the past year, as Arctic PIRE researchers worked to develop an appropriate set of indicators by which to measure urban sustainability in Arctic cities, the team wrestled with notions of “Arctic,” “urban,” and “sustainability,” for none of which is there a single, universally accepted definition. “Arctic” was settled on as being the region above 60˚ North, as a sort of average of the many geographical and geopolitical parameters that are used to define the Arctic. “Urban” is defined functionally as a densely populated area that serves diverse social, cultural, economic, and political functions, and has a minimum population size of 12,000 people. “Sustainability” is perhaps the most difficult to pin down, as noted by the volumes of research grappling with the concept. How should sustainability be defined, particularly as it relates to Arctic cities?

The 1987 Brundtland Commission definition of sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” has guided research and served as a driver for countless initiatives, though the definition is incredibly broad, and plenty of other definitions have been proposed. In the urban context, the UN Sustainable City Program defined the sustainable city as one that is able to retain the supply of natural resources while achieving economic, physical, and social progress, and remain safe against environmental risks that could undermine development. For Arctic cities, along with others, climate change presents a significant environmental risk to both development and the preservation of natural resources. As the Arctic faces these unfolding environmental changes, Arctic cities are facing similar challenges to other global cities in achieving economic, physical, and social progress. A sustainable Arctic city will be one that can meet its social, cultural, environmental, and political needs, alongside economic and physical objectives, while ensuring equitable access to all services by residents, without draining the city’s resources (Rogers 1997).

Brent Toderian, an urban planner and urban sustainability expert, proposed eight pillars of a sustainable city that represent some of the broader sustainability ideas but also outline concrete representations of sustainability in an urban environment, applicable to all cities, including those in the Arctic.

- A Complete walkable community in which mixed use facilities and mixed housing meet the varied needs of residents and various price points to ensure affordability, and the community is designed to protect the natural features.

- A low-impact transportation system that prioritizes cycling and walking, and incorporates many alternatives to single-person automobile use.

- Green buildings that use green design such as LEED, and include many multi-family dwellings.

- Flexible open space that accommodate both community and ecological needs including natural habitat, recreation, and space for growing food.

- Green infrastructure that addresses the supply and management of energy, water and waste, and includes innovative and financially viable heating and cooling options.

- A healthy food system that includes community garden space and food outlets, as well as preserving social and cultural food celebration, and incorporates other creative food-producing outlets.

- Community facilities and programs that support a healthy lifestyle for community members of all ages, that promote safety and well-being, and that foster community connection.

- Economic development including opportunities for business, investment, and employment, and includes a range of commercial facilities.

These pillars help to envision what a sustainable Arctic city would look like, and to begin to measure cities’ progress towards these ideals.