Asian Americans have been spat on, verbally assaulted and physically attacked in more than a thousand race-related incidents in the United States as a result of fear evoked by the COVID-19 pandemic. During a virtual town hall webinar, Alexa Alice Joubin provided a historical context for the discussion. She said connecting the language of disease to racism is not a new phenomenon.

Asian Americans have been spat on, verbally assaulted and physically attacked in more than a thousand race-related incidents in the United States as a result of fear evoked by the COVID-19 pandemic. During a virtual town hall webinar, Alexa Alice Joubin provided a historical context for the discussion. She said connecting the language of disease to racism is not a new phenomenon.

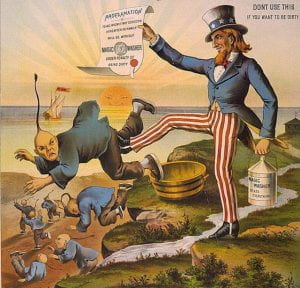

For example, it was seen in an 1886 soap advertisement “for kicking the Chinese out of the U.S.,” she said, and dubbed “yellow fever” in reference to white men who have a fetish for Asian women. The cartoon shows Uncle Sam holding a proclamation and a can of Magic Washer (a soap) while kicking Chinese out of the U.S. The caption reads “The Chinese must go."

Joubin said the language is associated with a history of discrimination against Chinese that made it into U.S. law, including the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Cable Act that prevented Chinese from becoming citizens even when they married U.S. citizens. It will take all of our cognitive ability, analytical reasoning “to concentrate and harness our resources to combat disinformation,” she said, “Our greatest fight is about fear.”

----------------------------------------------------------------

Excerpts from Joubin's presentation:

To combat anti-Asian racism in the wake of COVID-19, rather than serving up a harangue or diatribe, I propose we can increase our cognitive bandwidth by learning more about history.

In 1895, after China’s defeat in the first Sino-Japanese War, both Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and the Chinese scholar Yan Fu used the phrase yellow peril and the metaphor of a “sick man” to describe the Chinese people. In 1898, the concept became the title of British novelist M.P. Shiel’s short story Yellow Danger.

Punning on the disease of the same name, David Henry Hwang uses yellow fever in his play M. Butterfly (1988) to describe white men with a sexual fetish for East Asian women who are imagined to be subservient, dainty, and more feminine than their Western counterparts. Perceptions of Asian identities reflect the legacies of colonialism that seek to govern exotic bodies.

As it turns out, there is a long legal and institutional history behind the phenomenon of yellow fever and the idea of yellow peril. It goes back to the era of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was in force from 1882 to 1943, a time when whiteness became the dominant racial norm in the United States. Lily Wong has argued that the legalization of discrimination effectively marked Chinese workers “unfree and feminized laborers who undermine white workingmen’s ownership of their ‘free’ labor.” Chinese immigrants were both the desirable other in service of the United States and a codified threat. Female Chinese immigrants were assumed to be sex workers unless proven otherwise under the Page Act (1875) which was enacted under the guise of anti-trafficking laws. Similar restrictions were imposed on Indian women in British colonial Caribbean. At work here are both the “yellow peril” discourse and an imperial civilizing rescue mission.

Before 1922, if a female U.S. citizen married a foreign man, she would assume the citizenship of her husband and lose her U.S. citizenship. The Cable Act of 1922 partially amended the situation by allowing married women to retain their U.S. citizenship if their husbands were “aliens eligible to naturalization.” Asians were not eligible for U.S. citizenship, and American women who married Asian men would not be protected by the Cable Act.

As we have seen, race is profoundly constituted by language. It’s all about the words we choose to use.

Why is it important to understand the history of inequality during a time of crisis?

We need cognitive abilities to survive the global pandemic, and yet racism depletes our bandwidth for cognition. An example of the perils of losing one’s bandwidth for cognition during a crisis would be the people who run in the wrong direction when the house is on fire.

In high stress situations people rely more on their intuition rather than analytical reasoning. However, our intuition is influenced by our implicit biases that hinder deep thinking about issues.

COVID-19 does not discriminate, but racial discrimination adds undue stress to the society as a whole. This global public health emergency already threatens our ability to concentrate and our cognitive resources for important information.

Read the full coverage on GW Today (April 20, 2020). See also the GW blog.

Aw, I feel so bad for my son's college classmate who still gets bombarded with hateful comments from strangers regarding the spread of COVID-19 just because she's Asian. Thankfully, I found this article where you explained how such an issue can be traced back to the 1880s and how changes have been made ever since. Maybe I should watch a documentary to get a clearer understanding of this matter. https://theraceepidemic.com/