August 7, 2017

There has been a significant and steady increase in cannabis (i.e., marijuana) use in the U.S. between 2002 and 2015.[i] California was the first state to allow for medical use of cannabis after Proposition 215 in 1996. Currently, 29 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico have legalized cannabis for medical use, eight of which have also legalized recreational use. Results from a 2015 nationwide survey indicate that over 22 million Americans (>12 years) reported using cannabis within 30 days of the survey.[ii] Despite increases in use, there is a dearth of conclusive evidence around the harms and benefits of cannabis. This not only makes the topic difficult to discuss in a healthcare setting, but also contributes to a significant public health concern for at-risk populations. Recently on the Urgent Matters Podcast, Dr. Esther Choo (an emergency physician at Oregon State Health & Science University) spoke about her experiences working with a population that has access to legal recreational marijuana use.[iii] When asked if she includes marijuana use as a part of her social history she stated:

“The policy has outpaced our evidence base… We ask, and then what are we going to say?”

Dr. Choo highlights a thought-provoking dilemma that physicians face. The culture behind marijuana use is supported by public sentiments of both its health benefits as well as potential harms. However, physicians are not equipped with the evidence base to either endorse or recommend against it. As more states legalize marijuana, evidence around both short- and long-term health outcomes is needed to better inform patient-physician interaction and accurately evaluate the public health impact of marijuana use. So, how close are we to having a pragmatic discussion centered around cannabis with our patients?

The Evidence Base Around Cannabis and Cannabinoids

A 2017 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine offers an extensive review of relevant scientific literature surrounding the health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids published after 1999.[iv] While there is an abundance of information available in the 468-page report, some key conclusions that I find most informative with potential to impact clinical practice are listed below. I encourage you to at least read through the annex of the report for a summary of evidence-based recommendations on cannabis/cannabinoids and their impact on various cases such as cancer, cardiometabolic risk, respiratory disease, immunity, and mental health.

There is conclusive/substantial evidence that cannabis/cannabinoids are effective for:

- Chronic pain in adults (cannabis)

- Chemotherapy-induced nausea & vomiting (oral cannabinoid)

- Patient-reported multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms (oral cannabinoid)

There is limited evidence that cannabis/cannabinoids are effective for:

- Clinician-measured multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms (oral cannabinoid)

- Anxiety symptoms in individuals with social anxiety disorder (cannabidiol)

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (nabilone)

There is no or insufficient evidence to support or refute the conclusion that cannabis or cannabinoids are an effective treatment for:

- Cancers, including glioma (cannabinoids)

- Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (dronabinol)

- Epilepsy (cannabinoids)

- Dystonia (nabilone and dronabinol)

- Abstinence in the use of addictive substances (cannabinoids)

There is substantial evidence of a statistical association between cannabis smoking and:

- Worse respiratory symptoms and more frequent chronic bronchitis episodes

- Development of schizophrenia or other psychoses

Barriers & Future Direction

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report outlines many barriers to conducting research on the health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids. Any research around cannabis, a Schedule I substance, faces strict regulatory barriers. Additionally, researchers are often unable to obtain the quantity, quality, and type of cannabis needed to address specific research questions and draw scientific conclusions. If a physician is to prescribe cannabis, their patient should be well informed (i.e., starting dose, CBD vs. THC concentration, how to escalate safely, medication interaction, etc…). While we will have to wait for more evidence to make informed decisions on cannabis use, what about the legalization of recreational use? Does it impact healthcare? A 2017 study published in Preventive Medicine by Wang et al. raises the question:

Does the legalization of medical and recreational marijuana have an impact on hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and regional poison center (RPC) calls in Colorado?[v]

Wang et al. 2017

Dr. Wang and his team conducted a retrospective review of data collected from the Colorado Hospital Association (CHA) Discharge Databank and National Poison Data System (NPDS) data repository. The primary objective was to compare rates of hospitalizations and ED visits with marijuana-related billing codes and RPC calls with mention of marijuana. The secondary objective was to compare the primary diagnosis categories of hospitalizations and ED visits with marijuana-related billing codes to those without.

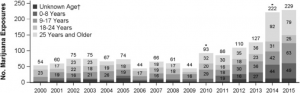

From 2000 to 2015, hospitalization rates with marijuana-related billing codes increased from 274 to 593 per 100,000. Interestingly, the prevalence of mental illness among ED visits with marijuana-related codes was 5x higher than the prevalence without – potentially due to the subsection of patients often receiving more detailed assessment around substance abuse habits, or having a greater number of visits to the ED. RPC calls remained constant from 2000 to 2009, but upon the legalization of medical marijuana in 2010 the number increased from 42 to 93. After recreational legalization in 2014, RPC calls increased from 123 to 221.

Figure 1: Rates of hospitalizations and ED visits with marijuana-related billing codes in the first three diagnosis codes in CO

Figure 2: Annual RPC human exposure calls related to marijuana in CO, by age group

Overall, legalization of both medical and recreational marijuana in Colorado is associated with an increase in hospitalizations, ED visits, and RPC calls. Since the study was conducted in a state with legalized recreational marijuana, the findings are likely generalizable to states with similar laws. However, as expected in such complex area, limitations do exist. Researchers relied solely on ICD codes and drug screens without conducting full chart reviews. Marijuana use cannot be viewed as the direct cause of most ED visits, hospitalizations, or RPC calls, as the effects are often short-lasting and not clinically relevant. The data provided does not establish causality between hospitalizations or ED visits secondary to marijuana exposure, and future research in this area should emphasize the importance of not overestimating the healthcare burden related to marijuana use. While researchers did well to establish an association between legalization of marijuana and increased healthcare utilization, there is still much work to be done in this area.

Key Terms

- Marijuana: colloquial term for the flowering plant intended for consumption. Used in discussion of Wang et al. to align with manuscript terminology.

- Cannabis: also known as marijuana, is the science-based term of flowering plant intended for consumption.

- Cannabinoid: a single class of diverse chemical compounds that act on cannabinoid receptors in the brain. The most notable cannabinoid is tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive compound in cannabis.

- Dronabinol: the international nonproprietary name (INN) for a pure isomer of THC, often used to treat anorexia in patients with HIV/AIDS as well as for refractory nausea and vomiting in people undergoing chemotherapy.

- Nabilone: a synthetic cannabinoid that mimics THC and is often used as an antiemetic and adjunct analgesic for neuropathic pain.

[i] CBHSQ (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality). 2016. Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50).

[ii] NCSL (National Conference of State Legislatures). 2016. State medical marijuana laws.

[iii] Pines JM. – Cannabis in the Emergency Department: policy vs. evidence with Dr. Esther Choo. Urgent Matters Podcast. 2017

[iv] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.17226/24625.

[v] Wang GS, Hall K, Vigil D, Banerji S, Monte A, VanDyke M. Marijuana and acute health care contacts in Colorado. Prev Med. 2017 Mar 30. pii: S0091-7435(17)30120-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.03.022.

Ameer Khalek is a MPH student at the GWU Milken Institute School of Public Health